Schools deal with students in some form of distress on an ongoing basis. That distress can be mild or severe, passing or persistent, free-floating or triggered in specific situations. Schools can often help, but often we need to seek more specialised guidance. It is, therefore, very hard to generalise much here; distress is an issue that needs individual attention if ever there was one.

However, making general statements is exactly how organisations must operate, and one can understand why in Sept 2015 the UK AQA exam board removed the topic of suicide – in particular Durkheims’ foundational study – from its A-Level Psychology syllabus. AQA wrote that it acted in line with its ‘duty of care to students… to make sure the content isn’t going to cause undue distress’. The motive is good – exposing students to topics that might trigger distress seems foolish, at first glance. But there are other views, and it was not a universally popular decision. Ged Flynn, Chair of Papyrus, a youth organisation saw this as irresponsible, writing ‘it’s been dropped because… [teachers] feel uncomfortable teaching about suicide… but suicide won’t go away if we feel sensitive about it.’ Philosopher Frank Furedi goes further than Flynn, and argues that even the motive of removing distress is misplaced; that ‘distress is not an indicator of illness; it is an integral part of people’s existence. When feeling distress is medicalised, young people are prevented from developing their own ways of coping with painful experiences’. According to Furedi, avoiding the subject is positively harmful to the students we are trying to serve.

This debate echoes the larger ongoing social one about the right and the wisdom of expressing views that offend people. From the Charlie Hebdo affair to the US elections, from holocaust deniers to far-right politics in Europe, from the Singaporean approach to multiculturalism to AQA’s decision – we can see this issue playing our time and time again in different ways. What is the balance between an open society and protecting those who need protection? It’s hard even to know how to begin, and the challenge is the one dramatised by Plato – that sometime reason and emotion can be two sets of horses pulling the chariot of our action in two different directions. So we may reason that if we are studying mental health we should know about suicide, for example, but we may feel distress in doing so.

These are not easy cases, but I suggest that we sometimes need to choose to put up with things we find distressing. In the case of students in schools, we know that small, limited exposure to triggers can be the best therapy for students, even if they feel otherwise; and we can support students through the distress, not just avoid it. For broader social issues, if we accept ‘it’s offensive’ as adequate justification for action then we are stepping away from reason, and allowing strength of feeling to be the decision maker. This is the route to extremism.

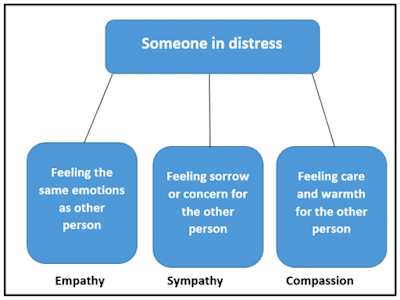

That’s not to say, of course, that there is no place for feelings in guiding our action. On the contrary, our feelings do and must underlie our reasoning; and we need to use compassion, where we feel for students to make reasoned judgements to decide difficult cases. Being parents, teachers or caregivers means having some distance, and some necessary perspective. Strangely, this means that in making decisions, we need to be a little wary of what is often a cardinal virtue – empathy, where we feel with people and try to adopt their worldview. Paul Bloom’s new book makes exactly this case – that for us to be too empathetic, to ‘vicariously experience… suffering, to [only] listen to our hearts’ is simply not good for those we are trying to nurture. “The alternative – careful reasoning mixed with a more distant compassion – seems cold and unfeeling. The main thing to be said in its favor is that it makes the world a better place.” This is familiar ground to parents, teachers and caregivers, who know that the ‘tough love’ that is needed is often not what is wanted.

References

- Bloom, P. (2016) Against Empathy: The Case for Rational Compassion. Ecco Books.

- Fox, C. (2015) I Find That Offensive London: Biteback Books

- Furedi, F (2015) Trigger Warnings are Educational Suicide Spiked 29 July 2015

- Guardian (2015) Suicide Dropped from sociology lessons – are some too topics too sensitive for school? 15 June 2015

3 Responses

Hi Nick,

Your post instantly reminded me of a TED talk by photographer Ryan Lobo (available here: https://www.ted.com/talks/ryan_lobo_through_the_lens_of_compassion). Perhaps in education, we are also responsible for the framing of controversial subjects–like Lobo and his photography.

Understanding and experimenting with 'lenses' isn't easy, but is necessary.

Thank you for sharing this.

Tricia

Thank you for a good post, Nick. I like your point about putting up with things that are distressing. As an adult, this is something we do all the time – to greater or lesser degree. Turning your blind eye to that is never the solution, so keeping young adults shielded from this is not the solution. Rather it is to expose them to it and teach them how to deal with it. /Morten

Thanks Nick for such a thought provoking blog this week. I agree that by keeping silent about difficult subjects make them shameful and taboo, leaving people ignorant. No matter how difficult and uncomfortable there need to be discussion. If these discussions trigger strong reactions, surely it would be a sign that a person needs help rather than burying feelings that manifest themselves in more destructive behaviours.