Some years ago we had a case of poor behaviour at school which led to a parent demanding very severe punishment for another pupil who had wronged his son. We resisted this request, because we thought that the misbehaving pupil was better served by supportive, though demanding conversation and a reflection on his actions (and of course we also supported the victim here). It seemed very clear to me, at the time, that this was the right thing to do, but the parent clearly felt we were abdicating our responsibilities to the other students – and his son in particular – by letting this behaviour go unpunished. Looking back now, some time after the event, the fact that the student in question has shown remorse, and not repeated the behaviour seems to be evidence that we were right in our approach.

But it’s not always so easy. In this case it was quite an extreme behaviour, and if it happened again then there would have been clear action to take. In other cases, it’s harder to know what to do. Here I am thinking of those cases where we see poor behaviours that are relatively mild in the scheme of things, but that keep going; things like being mean to other students, posting unkind things on social media, rude body language, missing lessons and so on. Any of these would normally require a conversation, and assuming students are open and willing to agree to change, nothing more. No single item would require a significant disciplinary response. But when these things mount up, without a single behaviour being repeated but with a pattern emerging, they are more worrying. We have a term ‘incorrigible behaviour’ for such cases, and this is grounds for serious action on our part. But it’s a troubling term because when the time comes to act, it is often for an apparently trivial item (such as being somewhat disruptive in an assembly) and a strong response appears disproportionate. The straw that broke the camel’s back seems to be an appropriate metaphor, but that is not always persuasive to the student and parents at this point!

There are, of course, ways to approach this; we have increasingly stern conversations, begin to involve parents, indicate that we are considering more serious action and so on. We are mindful that we need to show the broader community that we take our values seriously (it’s really important that others do not think we condone these behaviours); but against this we weigh the fact that if we take significant action then we may need to inform Colleges that we have done so (this is a requirement from some Colleges, and so a matter of integrity) and this may have long term consequences for the students.

|

|

|

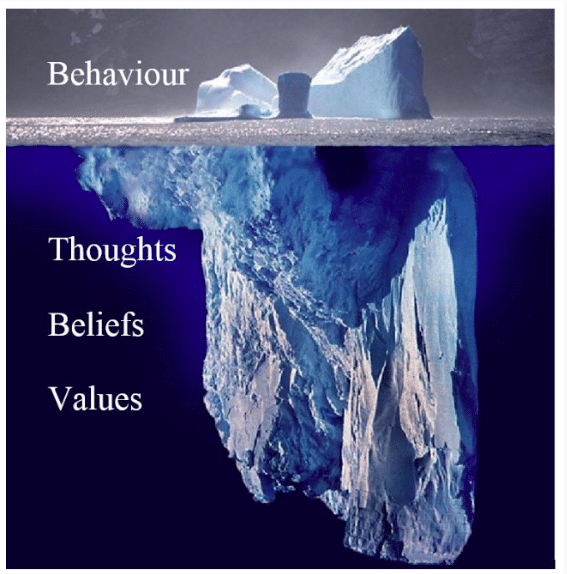

You can see that we like to exhaust all options in these cases. In other schools I have worked at, more severe consequences would follow more quickly, and so I’ve been reflecting on the matter at length. It really matters, for individuals, for our culture, for the trust we have with our community. We’re fairly liberal by many measures, but we are certainly not that caricature of a laissez-faire school (despite what the parent in my initial example thought). I have come to think that perhaps the most important thing is where we decide to place and focus our attention. We spend time with students looking at underlying values and beliefs that are implied by their behaviours, and usually try to give students space to find their own way (with support and nudging, of course). So things can take a long time and it can seem like we put up with a lot of ‘poor behaviour’ (of course in some cases, eg health and safety, we act immediately). But if for some students there seems to be no development in underlying values, as evidenced by a whole range of (different) behaviours, then there comes a point where we will have to begin to ask harder questions about the student’s place in an institution whose values he/she seems not to share.

I suppose the summary here, is that we seek a happy balance between being a rigid rule-bound school, and a laissez-faire one. That has a long and distinguished history, as American educator John Dewey said: Nothing is more absurd than to suppose that there is no middle term between leaving a child to his own unguided fancies and likes, or controlling his activities by a formal succession of dictated directions. For us, as students get older and closer to adulthood, we try to move toward the former, independent end of Dewey’s characterization, but we’re not afraid to invoke the latter approach when we need.

2 Responses

Nick, has there been any movement towards a restorative justice model at East? It's something that is in the early stages of gaining some traction here. If you've done any reading and have some recommendations I'd be interested to hear as I'd like to do some deeper reading this summer.

Hi – can we go to email on this one? Please drop me a line 🙂

N