Based in a country with a largely Confucian approach to education, Singapore schools and teachers enjoy great respect and support from the community. Measures of success are high, by the usual metrics of literacy, numeracy, standards of behaviour and high-end achievement. As the system here was built – like nearly everything – from a very low base over the last 50 year, nothing has happened by accident. It’s all been part of the grand strategic plan for Singapore, carefully designed to make and keep the country competitive and successful in the modern global economy. As a tiny country with very few natural resources, the talent and capabilities of Singaporeans has been the bedrock of the country’s success, and so education has always been and remains a top priority.

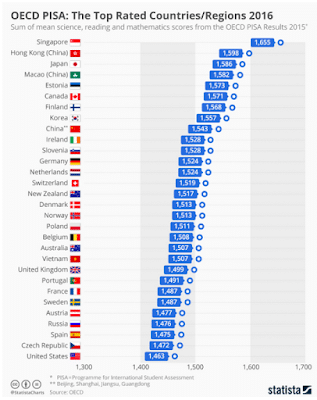

The education system is highly competitive, with frequent and public grades being used within and across schools to determine access to various streams at various points. This system frequently tops the international OECD PISA scores, as the graphic shows. We should therefore see the recent statement that ‘Learning is not a competition’ by Minister for Education Ong Ye Kung as more than a politician’s passing whim (as it might be in other countries). That the Ministry of Education (MOE) is looking to discourage competition shows a genuine and perhaps surprising desire for a change of direction. While the measures announced are relatively modest (schools will no longer indicate class rankings, for example) that Ong’s message follows his predecessor Ng Chee Meng’s emphasis on active Imagination, collective Inquisitiveness, and rich Interconnections indicates the continuity of message. So much so that Adrian Kuah Senior Research Fellow at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy has described it as a consistent and concerted attempt to transform the education system.

That really intrigued me, because when a couple of years ago I asked a very senior retired Singaporean civil servant about educational change, he said there were too many entrenched interests in the very successful system to change. But it seems he was wrong, and Singapore is indeed exploring the territory that some national and international schools and systems are occupy. Reducing competition in a competitive system is very difficult, because if you are in it, winning seems to be the whole point; coming in the top 20% and getting a place at the best Colleges, say, becomes the whole purpose of school. In the most extreme case the exams are taken to a nationally disruptive level, as if the country was there to support exams rather than the other way around. We see the same thing writ large in global politics, where winning seems to have become the purpose in itself, rather than the means to a greater good.

Unlike certain electoral politics however, Singapore plays the long game; there will be no radical change. Instead it will be a slow, step-by-step process of nudging an education system into the sorts of structures that can support students to develop increasingly complex skills. The current high-stakes primary school leaving exams are still in place, but taking Ong Ye Kung’s statement at face value, I wonder how long before that too comes into question.

Kuah’s analysis of this change describes it as disconcerting but necessary. The disconcering part arises because this is not a minor technical change of syllabus, butan adaptive change of values and even relationships. It is, ultimately, a moral endeavour. It’s worth quoting him at length:

The complex enterprise of raising a child, a dynamic collaboration between home and family, cannot be gauged by the simple measure of the examination and the grade, convenient and easy though it may be to rely on them…. these changes challenge us to level up as parents and teachers. They require us to raise, guide, mentor and develop our children without cleaving to distorting, single-dimension measures….for these changes to work, we – as parents, teachers, employers and so forth – need to respond by embracing these changes and rethinking our own approaches to parenting, educating and hiring.

I see it as little short of inspirational that a country already excelling in narrow measures is not willing to sell its children short by remaining narrow, and that it is moving toward the oft-quoted advice – don’t compare yourself to someone else today; compare yourself to who you were yesterday. There’s no doubt that academic excellence will rightly continue to be high up on the agenda, but it looks to be heading towards a broader more thoughtful manifestation.

References

- Kuah, A. W. J. (2018) Why the move to reduce examinations and emphasis on grades is disconcerting, but necessary Global-is-Asian, Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy

- Moon,K. (2018) The Korean CSAT is the exam that stops a nation. BBC News

- Wood, J (2018) Children in Singapore will no longer be ranked by Exam results. Here’s Why World Economic Forum.

- World Economic Forum Future of Jobs Report 2018