It’s been hard, over recent years, to read the news and to trust so many of the people often in it. From lies, to evasion, to obfuscation, to incompetence – there are many ways to lose trust. And a country without trust is headed in a dangerous direction. Equally, a high-trust society needs to stay on a positive trajectory; Singaporean Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong described trust as creating a “virtuous cycle .. that keeps Singapore on the up and not on the down” and pointed at George Schultz’s short piece on trust. Schultz, who held four US Cabinet positions and served in three presidential administrations, devoted himself to ideals of bipartisanship and fairness – building trust across political and racial divides. His description applies, I think, as much to organisations, families and personal relationships as it does governments:

When trust was in the room good things happened. When trust was not in the room, good things did not happen. Everything else is details.

Warren Buffet said something similar when he wrote that trust is like the air we breathe. When it’s present, nobody really notices. But when it’s absent, everybody notices so it’s worth paying attention to what is sometimes an unexamined facet of organisations. Here I am thinking less about whether or not we trust an individual (Stephen Covey’s famous model is very good for that) and more about what we mean when we even talk about trust. I have come to realise that the word can be used in very different ways, depending on organisational culture.

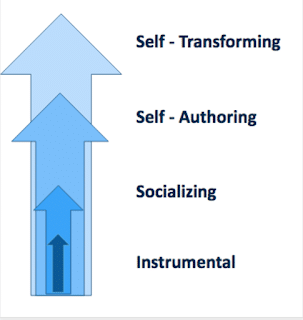

Building on Robert Kagan’s developmental theories, Bill and Ochan Powell have characterised a hierarchy of four types of organisation (instrumental, socialising, self-authoring and self-transforming), each one of which subsumes the others. Trust means different thing in each of these organisations.

When we are at the instrumental stage, we are very rule-bound and driven by policy manuals. In these cases, trust is generally to be avoided – we just follow the rules. Where trust does exist it is contractual; based on formal directives, minutes, terms of reference, and so on. Because the trust is so limited, conflict is highly damaging, and differences are resolved by power, creating winners and losers.

If we can get past this stage, we may recognise the need for a people focus. That can take us to the socialising stage, where we’ve replaced the rules but now equate trust with harmony and good relations. That may feel good, but it can lead to conflict avoidance, toxic positivity and ‘niceness’ as a focus and complacency.

These two stages are probably familiar as stances to avoid, and an initial resolution is also relatively obvious. At the self-authoring stage, the focus moves away from rules and away from individuals, to the purpose of the organisation, the Mission. This is a big step, because this Mission can then guide strategy and decision-making so that trust is based on professional mission-aligned relationships. It’s hard to overstate the importance of moving away from a narrow focus on rules or niceness, to a broader sense of needing to meet the Mission.

This all sounds good, so it’s interesting that Powell and Powell identify a further evolution – the self-transforming stage, where the Mission is less a goal to drive towards and more a shared aspiration that is systematically and intentionally woven into the fabric and daily decision-making of the school. Trust is manifested in expecting and supporting individuals to contribute to the Mission in fluid, flexible and autonomous ways. Conflict is welcomed, named and actively managed to surface and resolve differences and to actively build trust; and perhaps critically, the approach is likely to move from the complicated to the complex (see here for the difference).

These are brief descriptions of powerful and complex ideas (do follow up to know more) but they do show how the same idea can manifest differently in different circumstances, and even probably across different sectors of the economy. But it’s true that strong trust of some sort is fundamental and pervasive for any organisation to be successful. Without it, little is possible – with it, remarkable things are within reach.

References

- The OIQ Factor: Raising your school’s organizational intelligence (Bill Powel; and Ochan Powell)

- Changing on the Job: Developing Leaders for a Complex World Paperback (Jennifer Garvey-Berger)

- A summary of the Constructive-Developmental Theory Of Robert Kegan (Jennifer Garvey-Berger)

- Trust is the Coin of The Realm (George Schultz)