In the weeks leading up to the December vacations we’re probably all looking forward to a break from work. The feeling always makes me reflect on working, as opposed to not working, or leisure time. Having the choice here is, of course, a socio-economic privilege – but it’s still interesting to see how the concept of ‘work’ has spread and taken possession of our thinking. I have found myself using phrases like working on planning my holiday or working to clear the backlog of books to read or even I am going to be working hard on relaxing. One of my children mentions a chance to get ahead for next term’s work. A colleague describes getting a massage as bodywork; another discusses a long-overdue family reunion as a chance to work hard at re-building connections after so long, and I reply that I am working on my food and sleep habits. And so on.

Thus work seems to have become a general purpose synonym for doing. If that’s all it is – the inevitable evolution of language – then it’s probably pointless to lament it; but I can’t help feeling that there’s a bit more to it than that. The comments above, and the fact that many of us have to agree a ‘blackout’ time with close work colleagues, suggests that while we say we have work to do, sometimes, it’s the other way around – the work has us; we are in the grip of something.

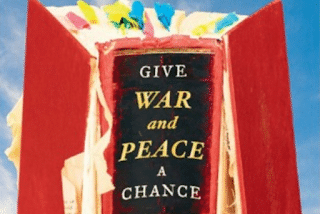

This is hardly a new observation. There is simply so much to do, so many demands to meet, so many worthy projects to develop that there seem few other options than to live in a pragmatic, utilitarian manner. But as Poet David Whyte says, the danger is that those who live in a pragmatic, utilitarian manner turn into utilitarian pragmatists. The ‘how do I succeed?’ questions quickly eclipse ‘why am I doing this?’ questions…. You begin to view yourself less as a soul to be uplifted and more as a skill to be maximized… [So] Work is a place you can perhaps lose yourself more easily than find yourself. It’s fascinating how easy it is to simply let drop those spiritual questions that used to plague you, to drop those deep books that used to define you, to streamline yourself into a professional person. When I look at the books beside my bed, that causes me pause for thought. But Whyte’s diagnosis, is, I think, limited. He suggests that the result of letting work be all consuming is acedia – the quieting of passion, the lack of care; it is living a life that does not arouse your strong passions… the person living in acedia might have a job and a family, but he is not entirely grabbed by his own life.

That may be an accurate description of some areas, but not, I think, of most schools or social professions and enterprises, which have what Martin Luther King used to refer to as work that has volume. Good work has length – something we can get better at over a lifetime; it has breadth – it should touch many other people; and it has height – as MLK says it puts us in service to some ideal and satisfies the soul’s yearning for righteousness. When work has these characteristics, it’s hard to imagine just switching it off for a break. But perhaps that’s the problem – and just because it’s hard to imagine does not mean that it’s not necessary. Thomas Merton, Trappist monk, poet, and social activist, suggested that an equally dangerous effect of work is precisely the opposite of acedia – more a manic thrashing around which he described as a pervasive form of contemporary violence to which the idealist most easily succumbs: activism and overwork…. to allow oneself to be carried away by a multitude of conflicting concerns, to surrender to too many demands, to commit oneself to too many projects, to want to help everyone in everything… neutralizes our work for peace. It destroys our own inner capacity for peace. It destroys the fruitfulness of our own work, because it kills the root of inner wisdom which makes work fruitful.

There may well be truth to both these extremes; different people respond differently after all. But both seem to be possible outcomes in lives where certain important professional-personal boundaries – which perhaps should be somewhat porous – have completely dissolved. Perhaps the main task this break is not to rebuild them (sounds like work to me) but to allow them some space to re-emerge and re-plant themselves in our lives, so that they can once again enable us, sustain us to be our best.

References

- Markman, A. (2017) How to forget about work when you are not working. Harvard Business Review.

- Merton, T. (1968) Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander. Penguin, Random House.

- White, D (1996) The Heart Aroused: Poetry and the Preservation of the Soul in Corporate America: Crown Business