It is hard to read the news and not hear about ‘the coming Artificial Intelligence (AI) revolution.’ What used to be philosophical argumentation centred around issues such as Can Machines Think? morphed for a while into quirky interest stories about humans being beaten in Chess, Jeopardy! and Go and has now emerged as worries about the threat of mass unemployment as jobs are replaced by machines.

As always, there is historic context here. Machines that can think are the latest in the trend whereby human physical labour has been replaced by machine labour. We drive rather than walk; we have washing machines rather than scrub in the river; we have ovens and no longer collect firewood. We are now increasingly often seeing similar things happening to human intellectual labour (I ask Siri for directions; I rely on machines for translations) and it’s not hard to see predictions of doom and gloom as things that used to require humans are done by machines. There is even real fear of AI as an existential threat to humanity as computers surpass us in intelligence.

There is optimism alongside the pessimism though. Some see AI as ushering in a new age of prosperity, with ‘clean water, food, and energy’ becoming freely available as machines solve human problems. There is historical context here too – previous Utopian predictions (such as ‘electricity too cheap to meter’ made available by the promise of atomic technology in the 1950s) have not yet coming to pass.

Between the extremes (here’s a great overview) lie all sort of possibilities. And of course the question for educators is – given the extreme uncertainty, what are we preparing students for, and how can we do it?

Popular images such as this one seem to miss out on two of the three.

The optimists would say that as machines free us from many tasks that are meaningless and drudgery, we need to prepare students for a life of leisure. I worry that we sometimes overlook the fact that leisure is best understood as the flip side of work – it has meaning by contrast. Not to say that the two are entirely separate, but a life of complete leisure would not, to my mind, be a hugely attractive one. We cannot give up on the task of preparing students for meaningful ways of making a contribution; for most, that will still look like having a career – at least for now. Others suggest that the march of the machines requires we orient our education towards coding and understanding algorithmic thinking. I am often lobbied by parents who ask why can’t coding be compulsory K-12 for everyone? However, it seems to me that if AI is the future, then competing in areas which can be reduced to a set of rules, codified and automated is hardly playing to our human strengths! Programming is surely one of the things that intelligent machines will be really, really good at! Trying to complete in this field would be like the original couriers, who ran with messages, trying to run faster to compete against couriers with motorbikes. That’s not to say that learning algorithmic thinking is not valuable – it is; but because it teaches us to think well and clearly, not because it will guarantee a certain future. So we will not be mandating our curriculum in that direction anytime soon.

So what are the professions worth pursuing? I have written elsewhere about the general features that will drive us to a life well-lived – but asking what professions will be around is nevertheless still an interesting question. Speculation is notoriously cheap – so here goes. Maybe we should not be looking at distinguishing between traditional and new work, or between the industrial and knowledge economies. Maybe we can distinguish between personal services and impersonal services. An impersonal service can be done remotely (offshored) and perhaps automated – as some radiographers, lawyers and accountants are finding. Some hitherto ‘safe’ professions are no longer so safe for this reason. For a personal service, however, a human really is needed. Princeton Economist Alan Blinder has noted that you cannot hammer a nail over the internet. He may be overlooking a future where robots are ubiquitous, so this is not necessarily a complete answer – but it’s interesting to note that there are signs that areas of real shortage are those involving plumbers, builders, roofers, chefs, osteopaths, physiotherapists (the latter, in the age of overused handphones, will always be in demand) and other skilled craftspeople. The experiences of my family members in the UK suggests that those in these areas are in higher demand than ever. As a teacher of philosophy and mathematics – two rather abstract disciplines – I hate to say it, but perhaps the dive into the knowledge economy has overprivileged the abstract over the concrete. Perhaps the days of the trades will be making a comeback.

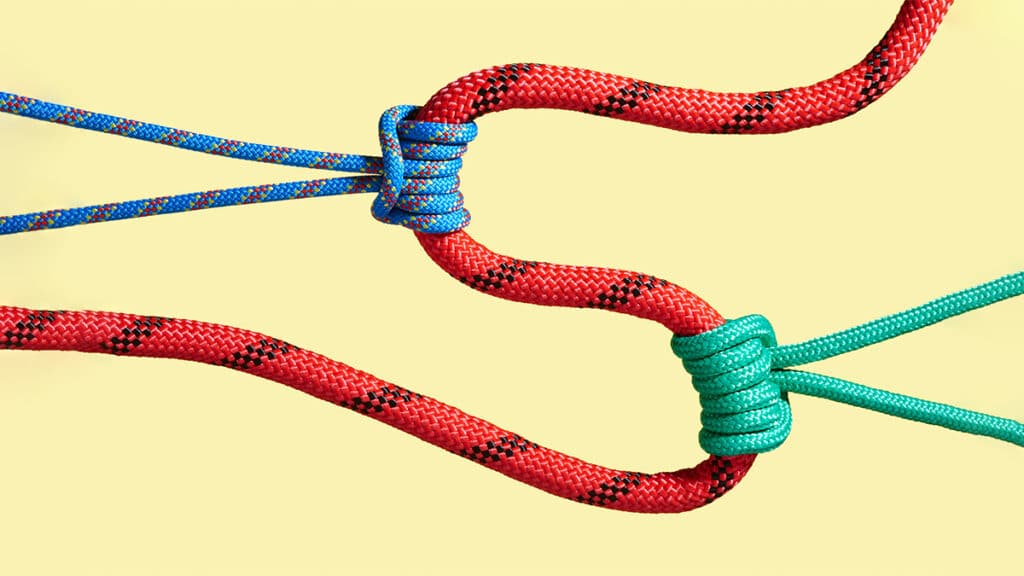

Progressive educators have long talked about head, heart and hands. Certain aspects of head-work may be vulnerable to AI; but heart and hand may be more resilient. We need to be sure that the education we offer develops students in all three areas.

References

- Urban, T (2015) The Artificial Intelligence Revolution.

- Ford, M (2016) The Rise of the Robots: Technology and the Threat of a Jobless Future. New York: Basic Books.

3 Responses

I do agree experiential learning is more important than ever as we train students for an AI-driven future where collaborating with machines might be the norm than the rule. We also need to assess and reward students for their creativity and ingenuity and they need to be formally built into their everyday learning. Both educators and administrators need to reevaluate the curriculum and the professional development where students not only find solutions to problems, but identify future problems and design appropriate solutions accordingly. To do so, one might need some understanding of one or more programming languages, but how can we leverage the combined human and machine power to identify new problems, say in disaster management, education, healthcare, traffic congestion etc. For example, could we create sophisticated forecast models for hurricanes in order to speed up the safe and early evacuation of millions in a big city? Can we harness the power of AI to design low-cost genetic solutions for cancer treatment? I guess we will still need educators, engineers, doctors, social scientists, but we might also expect them to reskill from time to time in order to successfully work and coexist with machines.

– Vee

Thanks Vee. It seems to me to be a central message from human experience that technical fixes look great in principle, but that human factors are what make the difference between success and failure. In your example – disaster management is classic case. So I agree, existence may be the way forward in these cases. Smaller, more local issues – reading an X-Ray, researching legal precedent – I imagine the co-existence will be 95%-5% in favour of machines.

Low-skilled repetitive tasks will be decimated and we are already witnessing this trend in several industries. Eventually we need individuals with multiple skill sets, not degrees with a single major, where they could hybridize their strengths to provide solutions to a niche market. For example, a medical engineer who could exploit his engineering and medical domains to build AI-driven scanners for hospitals or mathematicians who can help draft financial plans, or educator-counselors who could provide empathetic solutions to students' psychological problems in addition to imparting academic knowledge. Eventually we have to get outside our comfort zones to secure our future and as the IBO mission statement says, 'become active, compassionate, and life-long learners.'