It’s been really hard to know how to talk to students about the US elections. Listening to political ‘discussions’ I was reminded that discussion, percussion and concussion all have the same root – and certainly I felt as if people were trying to hit each other (and me) around the head with opinions rather than engage in some meaningful conversation. There are a number of perennial complexities here that have been especially difficult, I think, during this election:

- our duty to support students to make good choices, weighed against our need to respect their autonomy

- how to encourage open-mindedness without being naive or gullible

- how to support appropriate skepticism while not slipping into cynicism

- our need to stand up for our personal values while maintaining professional discretion

- the problem of distinguishing between political and moral beliefs

- the balance between the need to teach what we know is important against the dangers of indoctrination

- how to neutrally judge the (dis)honesty and (un)professionalism of a lot of media

The list goes on, and there’s so much to think about that I have found it hard to get beyond the most banal conversations. One thing that I have realised is that we have to work hard to keep whose side are you on? thinking out of our minds. I have a deep belief that High Schools should be in the business of teaching students how to think well, not what to think (even if we knew, that way lies disaster). And it therefore follows that we have to retain some degree of professionally neutrality, even while we can personally feel passionately. Naturally, students can often tell the difference, but there is a distinction to maintain – we in service of democratic values, not any specific party. I know not everyone agrees with this; when a political party or its representative seem anti-democratic, is condemnation not right? The trouble with this view is that the term anti-democratic can be, has been defined in many ways and can easily be mis-applied. Once we start throwing these terms about, it does tend to concussion, not discussion. That’s a dangerous tiger to ride.

I have also noted in myself and others the tendency to make the assumptions that good people would vote like me; and then the implication is that those who did not vote like me cannot be good. If we are not careful, we can quickly end up demonising the other side. We have a word for that which we would condemn elsewhere – stereotyping. Black-and-white thinking is the enemy here. We all have colleagues and friends whose affections lay with a different candidate; likely these colleagues and friends are good people. But it’s easy for the dominant discourse to silence these good people, and we have to avoid childish goody and baddy caricatures, which of course are fed by the echo-chamber of social media (everyone should read this rather shocking piece on that topic).

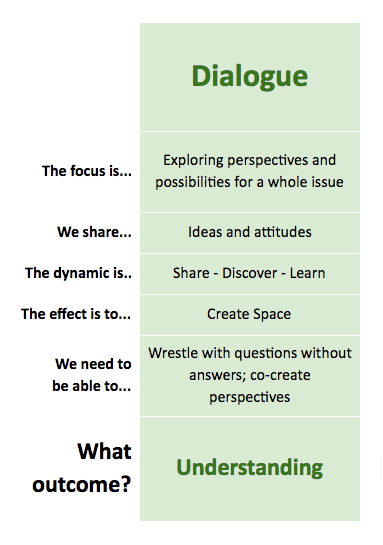

Our Mission at UWC is to make education a force to unite people. The Mission of the IB is to create a more peaceful world through intercultural understanding and respect. The underlying similarity is obvious. So given what I have said, what does this mean in this context? I think it means we need a lot more dialogue – that is, conversation without trying to convert, persuade, or judge; conversation that is simply aimed at deepening understanding. It may sound simple; it is not, as we have been discovering as we seek to embed this into the nature of our conversations. We adults need to learn it if we are model it; it’s very much work in progress, but it’s an intentional and powerful part of our culture now.

It seems odd to fall from grand global politics to the detailed nature of how we talk. But the way we talk was a huge issue in the election, and we have to teach our children to be capable of better than what they saw recently. This is not a new idea; there is so much known about the transformation that this kind of conversation can bring about.

For many years psychologist Jonathan Haidt has explored about the way liberals and conservatives view and talk about each other; his first TED talk outlines why and how they differ in fascinating ways, and his second one explores this specifically in relation to the US election, and touches on the ideas I describe here. Whichever way you lean, these are essential viewing for adults hoping to talk to children about why people see things differently, and to help them understand that other people, with their differences, can also believe that they are right. Of course, the problem of who actually is right will still remain – but this is a necessary first step.

——–

Since writing this, Chris Edwards, our Head of College has written very powerfully on this topic too. Please do take a look.

References

- Garmston, R. and Wellman B (1999) The Adaptive School: A Sourcebook for Developing Collaborative Groups: Norwood MA:

- Christopher-Gordon Glaser, J., (2013) Conversational Intelligence: How Great Leaders Build Trust and Get Extraordinary Results: New York: Biblio Motion

- Haidt, J (2008) The Moral Roots of Liberals and Conservatives (TED Talk)

- Haidt J (2010) The Righteous Mind: Why Good People are Divided by Politics and Religion; London Penguin Books

- Haidt J, (2016) Can a Divided America Heal? (TED Talk)