A distinguished Soviet professor of statistics was well-known for his refusal to go to a raid shelter during German air raids on Moscow during World War II, arguing “there are 7 million people in Moscow, why should I expect them to hit me?” One night he showed up, looking shaken, and his friends asked him what had changed. He said “Look, there are 7 million people in Moscow and one elephant. Last night they got the elephant” (1) A funny story, but you can imagine he might have taken away the opposite message – after all, what are the chances of hitting both the elephant and the professor? Surely he was safe at least for a few more nights!

The point here is that we need to be careful in interpreting data. Often you can draw whatever conclusion you like, and a lot depends on what data you track. The danger is that we focus on the high visibility elephants. It’s not a problem confined to education, and an example from healthcare is instructive.

In the USA hospitals use the concept of ‘survivability’ for ranking. Avery Comarow, health rankings editor at US News, said in an email that ‘30-day mortality is the most common benchmarking period used by researchers, insurers and hospitals themselves for evaluating in-hospital mortality, because it recognises that a hospital is responsible for patients not just during their hospital stay but for a reasonable period after they are discharged’. It’s great that hospitals are recognising that they need to track things after discharge, but it’s not hard to see that this measure is flawed. What if a group of patients lives only for 32 days after hospitalisation? Or lives longer but in great pain, or debilitated? Furthermore, do the rankings means that the hospital might chose not to admit very sick patients, and stick with the safer ones?

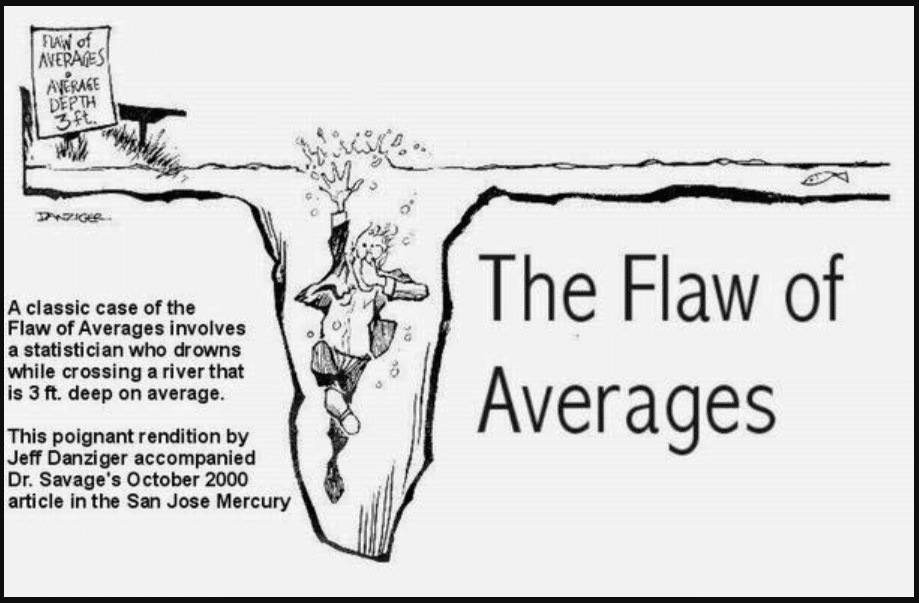

On average, therefore, they are reasonably useful.

I am not against collecting the data. Limited though it is, it’s better to know it than not; no one wants hospitals, schools or any other institutions where no one wonders how they are performing, or seeks to improve. But we have to know how to interpret the results, and not jump to conclusions.

In schools, we are often asked about our average academic attainment scores. In recent open days, we have been asked about average ISA scores for Primary and Middle School, and average IGCSE/DP scores for High School. I am always loathe to spend much time on these averages; because they are the elephants here – highly visible, and often highly misleading. Let’s ignore for a moment the fact that the most valuable things cannot be captured in examinations; let’s just remember that an average score is a summary that hides the individual stories, and institutional biases.

Individual stories are really what schools should be all about. Prospective parents should be asking will my child, who struggles academically, be supported to do as well as possible, even if he/she comes in below average? Or will my child who finds academics easy, be stretched and not allowed to coast? These and similar questions both come down to moving beyond averages.

Institutional biases can also make the averages misleading. Schools which ask academically struggling students to leave, or which select on purely academic grounds, or which narrowly teach to pass tests rather than instil understanding, will get higher averages than those that do not. But these are not, I would suggest, necessarily things that are serving the interests of students. Once again averages mislead.

So what can we go on, if not average data? Here’s some alternative data that I found useful; I had the great pleasure of hosting an alumni reunion and hearing stories from some 150 recent graduates, in London. Many had come from all distant parts of the UK, and a few had come in from Holland. They were so incredibly appreciative of what they had experienced at the school, and how they felt it had set them up for College, that I was tempted to feel a bit pleased, and perhaps even self-satisfied. But then the term confirmation bias entered my mind, and I wondered how many students did not want to come to the re-union, or I had not managed to speak to, or who had not told me things for fear of seeming rude.

What all this adds up to is that there are no easy ways to summarise complex organisations. My message to prospective parents is always to have multiple conversations with students, teachers and parents, to visit schools, and to treat simple data with great skepticism.

References

- Bernstein, P. (1996) Against the Gods: The Remarkable Story ofRisk. New York, John Wiley and Sons