When my wife did karate at school, the instructors made a point of promoting gender equality. With all the authority of a fourth dan, Sensei confidently declared in a deep voice there’s no place for sexism in the dojo. He glared challengingly at the boys, and said girls and boys can both do karate, and some girls are actually quite good at it.

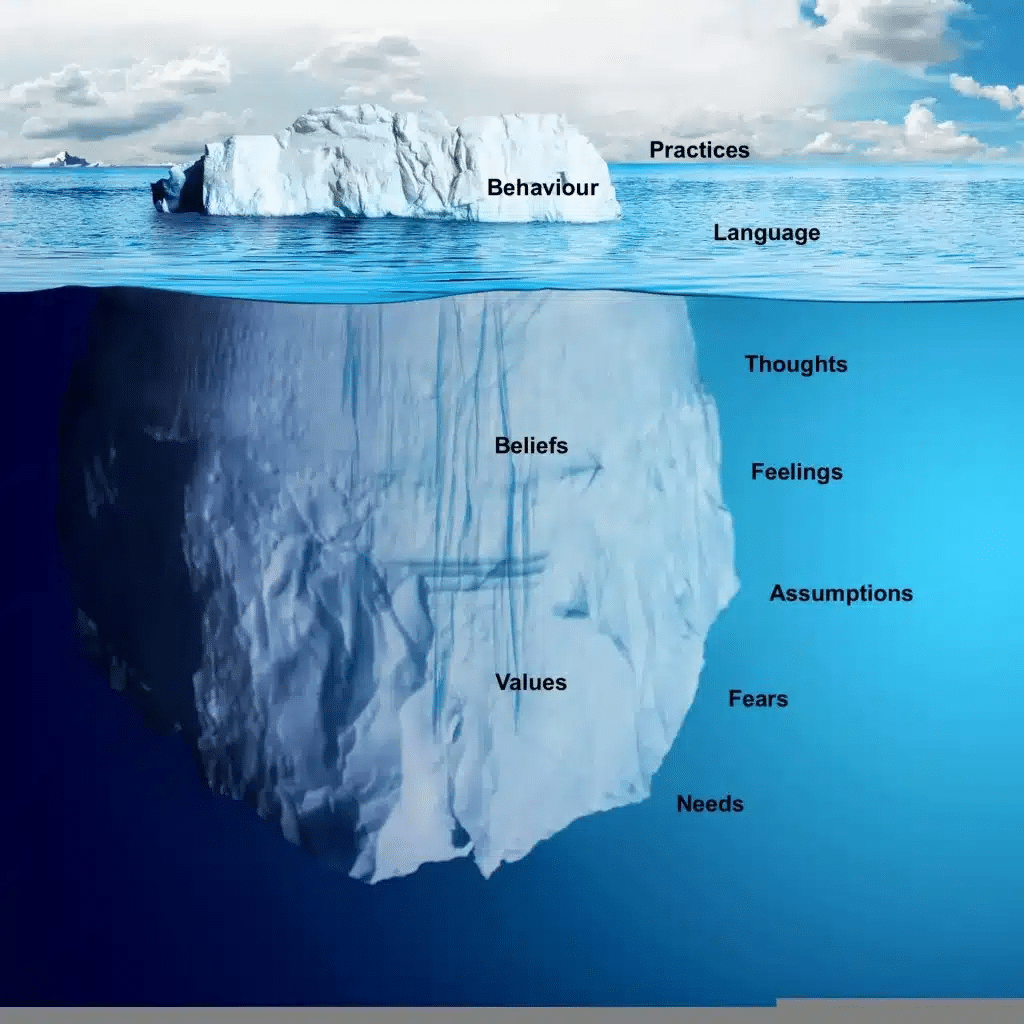

This is easy to laugh at, or perhaps easy to get angry about; but there is certainly a gesture towards equality here. And this is a well-known phenomenon – that we can believe in and advocate for a certain set of values and understandings, while at the same time having some deep assumptions and drivers that push us in very different directions. The most extreme example of this that I know about is Isaac Newton; despite being a key figure in creating the modern scientific outlook, he still pursued the occult with a passion (there’s even a Wikipedia page devoted to it!). Perhaps he was, therefore, more the last man of the old generation, rather than the first man of the new. The thing is here that we all have cognitive ‘deep structures’ that we do not even know about. Under this model cognition is commonly depicted as an iceberg, whereby we are only conscious of behaviours above the waterline, and not of the assumptions, beliefs and even hopes and fears below it.

We sometimes see the same thing in education. Many of us know that we do not want for our children what we had; authoritarian, top-down, narrow academic learning. We want an values-based education that prioritises learning to think over narrower, multiple-choice measures. We want a system that develops creativity, that can deal with ambiguity and that focuses on deep understanding (these are, after all, the things that are needed after school life). But then we sometimes ask why we don’t give more ‘rigorous’ testing much more often, with clear outcomes, like percentages, so we can compare students with each other. There is a place for tests, for sure, but less than we sometimes think. It’s not an accident that our most complex, intellectually demanding course (Theory of Knowledge) has no exams whatsoever – and really, when you look at the work an average class produces (examples) you can see why an exam is simply the wrong way to assess here. For this kind of thinking, exams may look like academic rigour, but looks can be deceiving, so we need to be a bit more nuanced than that.

So we’ve been trying a few things; they don’t look like normal assessments, and they’re going well. By chance I happened to be speaking with two students who have just completed such an assessment (as part of the Systems Transformation pilot course that we are doing for the International Baccalaureate) and I asked them to say a few words about it, and to pass some feedback to the assessment designers.

So what did this assessment look like?

This particular assessment had been designed as a day-long experience where students engage with an unseen case study through a series of individual and collaborative activities. They were given multiple sources of information about a complex social or environmental issue, and they explored it through activities such as a stakeholder mapping exercise. Perhaps one of the surprising things is that this assessment is designed to look and feel less like a traditional exam, and more like an extended version of the things students do on a day to day basis in their classroom. So if you walked past the door and looked inside you wouldn’t see students sitting in rows in a silent exam hall with just an ominous ticking clock, but students talking, laughing, discussing, exploring.

Is this a lesson or an exam?

One of the other assessment tasks for this pilot course involves students pitching an idea for a project to a panel consisting of a teacher, a peer student and a community expert, and showing how they have incorporated feedback into their project designs.

This work is a ringing endorsement of the possibility of a change to a more holistic approach to assessment. There is a lot to iron out and it’s not quite clear what is scalable and not, so this is very much work in progress, but I think it is promising.

I am not against traditional exams per se. My argument is that we need to align our school practices with our modern understanding of education – and that means better testing, not just more testing. If you listen to what these students are saying, then you can hear it is possible to combine rigour, relevance and even excitement and enjoyment. To want modern, progressive education and then to always reach for tests, regardless of context or purpose is like Sensei and his dojo, or Newton and his alchemy. I’m delighted we can do better.

1 Response

Nice Post!

SAT Exam 2024 in India