I recently wrote about the importance of competition; that is provides not just motivation, but also some opportunities for learning that are not so easily available elsewhere. I know this sits poorly with some educators, but I believe there is no necessary tension here with a simultaneous belief in co-operative learning. Co-operation and competition only seem opposed when viewed through a single narrow lens, which is increasingly limited.

The educational emphasis on co-operation has been described to me by friends in other sectors as rather idealistic, and a bit of a luxury that educators can indulge in but for which there is no room ‘in the real world’. This notion that we can always get better results by competition is perhaps inspired by analogy with biological evolution, where ‘survival of the fittest’ blurs with notions of ‘nature red in tooth and claw’ and familiar images of a leopard bringing down the slowest zebra; to live, all the zebra needs to do is run a little faster than another zebra. And so we are all competing with each other, and another’s success is a threat to us. The analogy is compelling – especially if you are a slow zebra – but it can be misleading to take it to far – largely because the human world is so much more complex than the animal world.

Of course, the notion of competition does have something going for it – in my previous post I wrote about a basketball game where one side winning means the other side losing – a so-called ‘zero-sum game’. But even there, note that within each team, each player has much to gain by co-operation – in fact, any player who does not co-operate with teammates will be quickly taken off. Within the team, survival of the fittest means cooperation, even though a competitive basketball match is a classic win-lose scenario.

I think a lot comes down to how we understand the term ‘fittest’. For the zebra avoiding the leopard, physical fitness may be an individual thing. It may once have been so for humans too – perhaps once the strongest or fastest won the biggest rewards – but it seems less and less likely. Surely today, fittest means better able to live and work in an increasingly complex world where no one person can understand everything, and where we have to rely on others to get anything done. That’s a recurrent feature of the global, interconnectedness of today’s society; we seem to be more a world where competition is more between teams than between individuals, and so for individuals, co-operation is a better, ‘fitter’ approach.

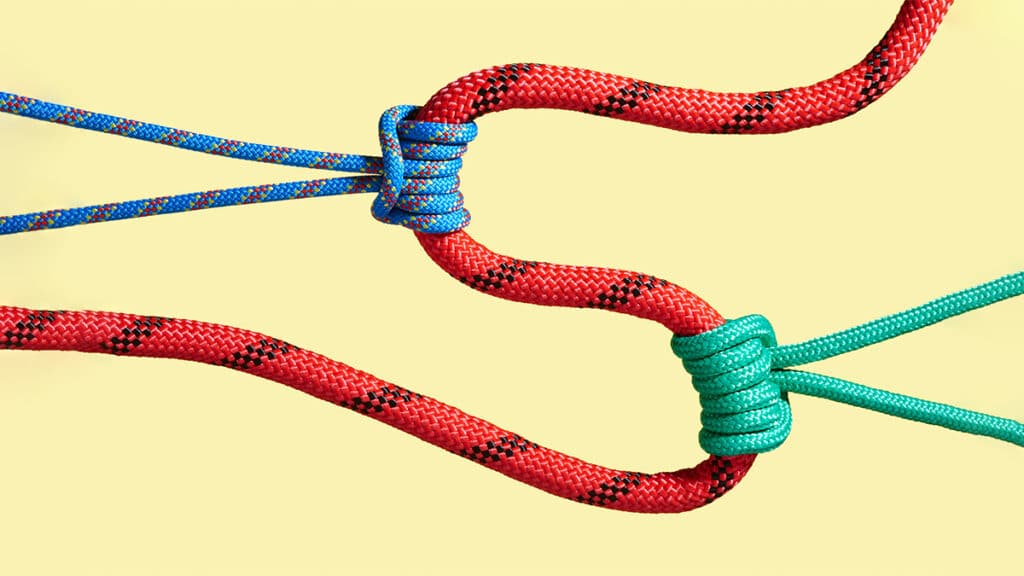

If that’s right, then perhaps we should focus more on ant-colonies or huddling penguins as our metaphors for evolution; and go with biologist Martin Nowak who has suggested we understand ‘survival of the fittest’ less as competition as a ‘snuggle for survival.’ And that may mean that learning how to co-operatively collaborate – which I understand to mean knowing how to achieve more in a group than as any individual – may be the most important thing that students can learn from their education.

Clancy, K (2017) : Survival of the Friendliest