Decades of research generally support the conclusion that children do better at school when their parents are involved in their education. However, exactly what form of involvement is most effective has been much disputed. Is active supervision of homework the key? Attendance at school functions? Rewards for high grades? Rewards for effort? Punishment for failure? A rich cultural life around museums, theatre, music, art? Out of school tuition? With so many variables – and differing cultural expectations – it is hard for parents (whose own children of course form a very small sample size) to know what works and what doesn’t.

But the research is gradually coming in; and it shows that some practices are more effective than others. The picture is not what you might expect. Researchers Robinson and Harris (2014) looked at academic attainment as related to specific parental involvements. It turns out that the two seem to be unrelated in 53% of the 1,556 cases they examined; which is to say that most actions we take as parents seem to have no effect! Even more worryingly, there were more negative associations (27%) between parental involvement and achievement than positive associations (20%). Even if this research is somewhat off the mark, it does suggest that there is a lot of wasted effort going on. This counter-intuitive finding is in line with a series of recent Singaporean studies which show that children who received tuition in Maths, English and Science actually scored worse than those that did not – even after adjusting for differences in students’ age, gender, home language, family structure, schools, parents’ education levels and employment status! Coming from one of the tuition capitals of the world, this is a fascinating finding, and one that we should pay close attention too (see here for why tuition can be harmful).

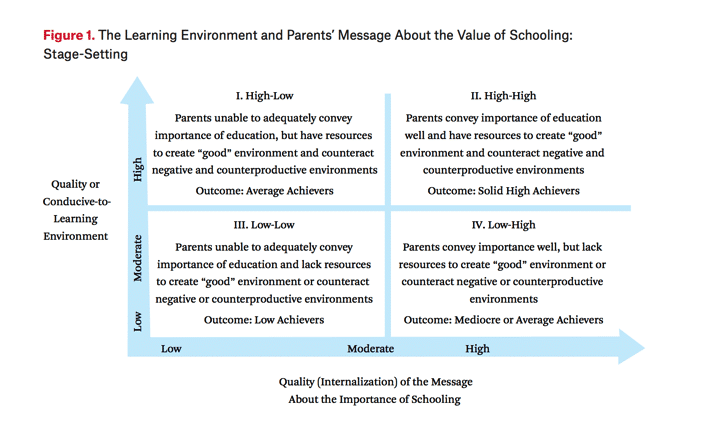

All this, and further research from Jaynes (2011), suggests that “traditional measures of parental involvement fail to capture the fundamental ways in which parents actually help their children academically”, and goes on to suggest “that parents focus on only two factors: messages and life space.”

Messages: Communicating high expectations. This seems so obvious – most parents express that education is important. But some parents are able to make this message more central to their children’s own academic identities, so that they come to internalize high aspirations for themselves. It’s probably easier to explain what this is not. It’s not nagging about homework, which “gets the job done, but doesn’t improve achievement”; because when schoolwork is a chore to be finished under duress, it’s about parental wishes, not internal student identity. As such, it is of little lasting value. Nor can we communicate high expectations by simply talking about school; dinner table conversations of ‘so what did you do today?’ have little impact on student success; in fact, one ex-student in the research noted “her parents rarely talked to [her] about school, did not help with homework, and did not read to [her]. Despite their lack of involvement, however, her parents had high expectations and [she] knew from an early age that doing well in school was important.”

So should we, as parents, communicate high expectations? It turns out that the mechanism here is subtle. Harris and Robinson suggest not thou-shalt-go-to-college edicts, but rather, as “everyday enforcements of the value of education, sacrifice, and hard work that students come to internalize as high aspirations for themselves.” More precisely, they argue (persuasively, to my mind) that “… certain aspects of their [family life] reinforce the importance… [of] education or living a “life of the mind”: having a home office, regularly reading [high quality] media, hosting occasional dinner parties, effortlessly (and even obliviously) engaging in (or enacting) critical thinking in common everyday discussions”. This is subtle, far reaching, and is the causation that underpins much of the well-known correlations between socio-economic status and academic attainment. We need to take careful note here.

Life-Space: Creating a high-quality learning environment. It is obvious that parents have a massive say on the physical home environment. And the key is what we as parents do, not what we say. Harris and Robinson again: “…each decision as to whether to have a television in a child’s bedroom, whether to put a desk in the child’s bedroom or in a more common area, or whether to have bookshelves in the living room or a home office communicates nonverbally something about the importance of learning.” There’s probably even more to it than that – are the children’s desks spacious, well lit with comfortable chairs? I have taken the expensive – but I hope valuable – step of allowing my kids to buy any books they want, as long as they tell me what the books are (easy on a family kindle account), and guarantee they will read them if I buy them. A small step, but I have seen the amount they read shoot through the roof. I also make sure my kids see me read each day. Small things, but powerful ones.

These two themes suggest that as parents, we can feel a little liberated in how we support our kids. Harris and Robinson asked a group of successful ex-students, “Did any of your parents read books to you when you were a child, attend PTA meetings, regularly converse with your teachers, or discuss college plans with you?” Many students shook their heads, and a male student recalled, ‘My parents didn’t do any of those things with me.’” That’s not to say that we shouldn’t do these things, of course, but to focus on specific tasks and behaviours misses the overall point. The deeper, more profound parenting come from the tens of thousands of daily interactions – in conversation, and in unspoken environmental ways.

References

- Harris, A. and Robinson, K. (2016) A New Framework for Understanding Parental Involvement: Setting the Stage for Academic Success. The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences. Volume 2, Number 5, September 2016, pp. 186-201

- Jeynes W. H. (2011) Parental Involvement Research: Moving to the next level. The School Community Journal. Vol 21 N0. 1 p 9 -18

- Marzano R. J. (2000) A new era of school reform going where the research takes us. Aurora: Colorado: Mid -Continent Research for Education and Learning.

6 Responses

Thanks, Nick. As always an inspirational piece.

It’s clearly a complex topic with no easy answers and often driven by cultural expectations.

So, as a father of two sons, here are my thoughts on the topic:

The aspect of being present is more to do with your mental presence than your physical presence. You can my physically presence without being there..

Taking a leaf out of the swim coaching that my kids are fortunate to attend, there is a video on YouTube of a TedTalk by John O’Sullivan – well known football coach in the US – talking about how you motivate your children: https://youtu.be/VXw0XGOVQvw

the key is not to judge them on how they do and what they do – but rather the message of telling them that ‘you love watching them play’ irrespective of the result. The key being that as a parent you do not know the sport, the stage they are at in the cycle, the instructions they received etc etc.

My point is: could this be applied to general school? I am not an educator, I do not know chemistry except for what I remember from high school a long time ago. Math is taught very differently from how it was taught back when I was a kid.

So is the most important role as a parent to excite our children about going to school? I think it is.

Thanks Morten. I am very much struck by what you say – "the key is not to judge them on how they do and what they do ". What we know is that when people feel judged, they often stop taking risks, they often focus on narrow (often ill-conceived) metrics of performance, and they often find that extrinsic motivations have squeezed out intrinsic ones.

I think that related closely to this idea that the best thing we can do for kids is to help them *internalise* high expectations (and positive beliefs) about school. And that’s why as educators we seek to make school a safe and secure place emotionally, why we try to make our lessons engaging, varied, interesting, fun, and why we try to speak about the *why* as well as the *what* to students.

Thank you for sharing your article Nick. The research outcomes are similar to what I have found delivers the best outcomes in the workplace too i.e. if you create the right conditions for success then employees feel empowered and tend to outperform, whereas heavy managerial oversight tends to lead to a culture where ideas and creativity are snuffed out, few risks are taken, and employees' self-growth becomes limited.

I clicked on the link within the article "see here for why tuition can be harmful" and was not surprised to see the very high (and growing) rates of extra tuition in Singapore and other Asian countries.

As an employer here in the Asia region what we see as missing in the talent pool of graduates is not students with high IQs (they are plentiful), but students with more EQ: more critical thinkers that can solve complex problems, present solutions to those problems and build teams of people that can do the same.

With the continuing development of artificial intelligence a person's IQ I believe will be less valuable because machines are more intelligent, whereas a person's EQ will be correspondingly more valuable, as machines are not good at emotion (not yet at least!).

Gerry Ball, UWC PARENT

Thanks Gerry; I think you raise the fascinating point that surely the best way for any organisations in any sector to excel is through its people. And not just by getting the 'best and brightest' but by creating a system whereby all individual have autonomy, purpose and opportunities for mastery. Then they will seek out opportunities for them and the organisation to grow, and this will fuel those feelings of autonomy, purpose and opportunities for mastery…. and we have a virtuous circle. Any alternative top-down, rule based organisation may succeed in a static environment, or where tasks are relatively simple and easily executed – but it is not likely to ever reach world-class standards.

It does not take more than 5 minutes talking to someone about where they work/study to find out how they see their organisation. And in any era where talent is short, it will seek those organisations where they can best flourish. So there are compelling practical as well as moral reasons to move in a specific direction.

Hi Nick,

Thanks for this article. I read it with great interest (even as a non-parent!) as the burden of tuition on students is a constant worry of mine! Just a brief comment – this whole articles gets me thinking along the lines of how parents should try and be 'coaches' for the children (asking the mediative questions about daily events etc.) rather than the evaluators. One example might be the homework piece you mentioned. A coaching approach might be, "I see your teacher emailed me about not doing your homework. What might be…." as opposed to "You haven't done your homework. You need to do your homework otherwise you won't learn". Forgive me for the basic example but I hope it gets across the idea that perhaps a parents role should be to help children think, rather than to evaluate them.

Louie

Hi Louie

I could not agree more. It's harder for parents in many ways though, as we have seen our children grow from needing a great deal of direction and help as babies/toddlers etc. So this is all mixed in with kids growing into independent adult, and the notoriously difficult teenage years at home. In high schools, by contrast, studnets enter in grade 9 already relatively independent, in most cases.

All this speaks to the point that it is our *identity* as parents – coach or evaluator – which is really at issue here. If we can find safe and appropriate ways to be coaches even when our kids are small, it will be natural part of our relationships and likely carry forward in the teenage years.

Of course, as a teacher I can write that. As a parent I know how hard it is to actually do.

Thanks for the comment.