In 1680, the English King James told architect Christopher Wren that the newly-completed St Paul’s cathedral was “awful, artificial and amusing”. In 1680 ‘awful’ meant ‘awe-inspiring’; ‘artificial’ meant ‘artistically made’ and ‘amusing’ meant ‘amazing’.

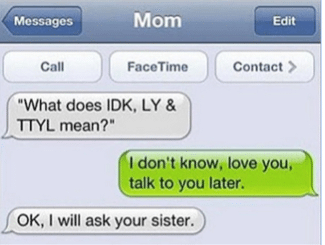

These flippant examples may seem a bit obscure – but a quick internet search for funny grammar images (here’s a good one) shows that the issue of correct or incorrect language raises strong emotions. And I was marking TOK essays from my grade 12 class last week, and wondering to what extent I should correct split infinitives, or allow sentences (like – ahem! – this one) to start with a conjunction. More importantly, I was wondering if examiners would see through informal writing to the genuinely profound ideas in the essays – and so perhaps there is a genuinely more serious point here. Outside of language acquisition course, there is nothing in most IB/IGCSE marking criteria about good grammar – and when we have so many students being examined in English as a second, third or fourth language, that’s got to be right. On the other hand, accuracy in communication is important, and grammar facilitates that. As a child I was always taught that ‘breaking the laws of grammar’ is a bad thing. So do these laws of grammar matter? I have come to think that the answer to this centres around what we think about the nature of laws, and I am reminded about how much we construct the world around us, rather than simply find it, already made. I think there’s actually a moral point here too.

So my visceral disgust at double negatives may not be without logical reason but the fact is that people do say “I ain’t done nothing wrong” and we all know what they mean, n’est-ce pas? Similarly, the word ‘like’ has recently evolved into an all purpose linguistic swiss-army knife, capable of remarkable flexibility (great article here). King James would have thought that was awful; to me, it’s awesome – and we both know what we are talking about. Languages change, and there’s nothing we can do to stop them. What’s more, language drift is a one-way current (for more on that see this wonderful book or watch this short TED talk).

As linguist Cukor-Avila said, “I tell my students, eventually all the people who hate this kind of thing are going to be dead, and the ones who use it are going to be in control.” While that may not the most uplifting sentiment, it is surely accurate.

Does that mean we don’t bother correcting students’ written work from infelicities? Of course not. Some styles are better suited to some occasions than others – and using “c u l8 r” in an English examination is a choice; probably not a very good one (texting is a fascinating dialect). So we need to be aware of the various universes of discourse that are available to us. I have come to see that rather than correcting students’ work (which can be perilously close to telling them how to conform to arbitrary social mores – hardly the right message) I am seeking to sensitise them so they can make the right choice choose to convey their message to their audience. In most cases, that will look like traditional correcting, but I think there’s a world of difference. Literally.

I remain your humble servant / BFF (delete as appropriate)

Nick