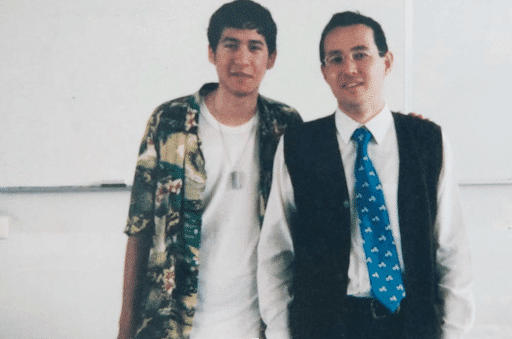

I attended a wonderful alumni event last weekend and saw a lot of people (online) that I hadn’t seen for many years. Afterwards, one ex-student, now approaching his 40s, sent me this picture taken on his Grade 12 Leavers Day in 2001 (thanks Kelvin!). As he and I have stayed in touch over the years – through some ups and downs – it got me thinking about the boy he was then, and the man he is now, and all the events in between.

Of course, we are all in a similar position; 20 years is a long time in any lifespan and the sense of distance between now and then is such a familiar one that it should have a name. Author and activist Rebecca Solnit writes sometimes an old photograph, an old friend, an old letter will remind you that you are not who you were once, for the person who dwelt among them longer exists. Without noticing it you have traversed a great distance; the strange became familiar and the familiar if not strange then at least uncomfortable – an outgrown garment.

When that photo was taken, I was a new father to one infant (I now have three children, with two graduated); I was a son to two healthy parents (now, only one, as my father died in 2020); I was a teacher of classes of students (now, a Head of School); I was improving my running times (now in precipitous decline); I was impatient and impetuous (less so now, though that may be a surprise to some!); I had lived in two countries (now four); I refused to take dress-sense advice from my wife (I have learnt the error of my ways). I was, in short, a very different person. As I look to the future, I wonder who I will become. And of course, that’s the question we are always asking about our children and our students: who will they be in decades to come? How can we help them see the possibilities and choose the best ones?

As any parent knows, it’s a tough question to ask, because the nature of this type of change is that it is transformative; what changes is not just our physical bodies, but our very selves, our values and hopes – which is to say, the very measures by which we might hope to understand and guide any transformation. By recognising that, we are recognising that the standards, ideas, aspirations by which we navigate are unstable, evolving; that the maps themselves (and not just the landscapes) change when we travel.

This means that the course will always be somewhat uncharted. It’s not a new problem – in the Meno, Plato asks How would you go about finding that thing, the nature of which is totally unknown to you? and it means we are always a little lost. Looking back, I can now see that I had only the vaguest idea of the course in which I was headed. Even though it may have seemed clear at the time, in truth the clarity comes with hindsight. Looking forward, therefore, the situation is surely similar.

So the questions we ask our children are always the same ones for ourselves – how are we changing? What touchstones are falling away? What new ones are emerging? Who do we want to be? What might matter to us in the future that does not seem important now?

We see in our children some rapid changes as they grow; in some cases it’s a slow evolution, in others it can be a rapid and sometimes painful discontinuity, especially in the teenage years (Solnit: some people inherit values and practices as a house they inhabit; some of us have to burn down that house, find our own ground, build from scratch). I’m thinking of those who suddenly find a passion, a cause, or an aspect of their identity that they need to step into; or indeed one that they need to step away from.

Overall, that some of the things we value will change is undeniable. The intrinsically transformative nature of this process means that all we can hope for is to find and hold onto some golden threads that survive across time, but that might manifest in different ways as we mature. So what might be the golden threads that can survive across the decades?

It’s an old problem, and the best answer seems to be from Freud: The healthy adult is one who can love, and who can work (where work is understood to be all our productive activities, paid or unpaid). Love and work… work and love. That’s all there is. Whatever else you might think of Freud’s ideas, there is no doubt he is onto something here; and it’s important we convey this to our children and students by both the things we say and the example we set.

References

- Paul, L. A. (2014). Transformative experience. Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press.

- Solnit, R (2006) A field guide to getting lost. Penguin Books