Students often ask why do we need to know this when we can just google it / use AI? It’s a great question, and it might indeed seem that with the internet as the fount of all knowledge, with facts only ever a click away, that there is less need to commit them to memory. It also seems to fit with the correct claim that creativity, critical thinking, communication, collaboration and other skills (some of which do not begin with ‘c’) are what we should be seeking to develop in our children, and we should therefore leave knowledge acquisition to focus on them instead.

However, the conclusion that knowledge is no longer important is profoundly mistaken for several reasons. I don’t want to focus here on the fact that relying on the internet for facts seems to have pushed us down a rather dark extremist path in recent years, or on the hallucinatory inclinations of AI – but rather on something more fundamental to our cognition. The point is the rather counterintuitive one that it is precisely because skills like creativity and critical thinking are so important that we also need to concentrate on knowledge. Let me explain, using examples from psychologist Daniel Willingham.

Suppose I told you that I have a house beside a small lake, only 40 feet from the water at high tide. Would you believe me?

When I came across this example I didn’t really see the point. But that’s because I didn’t realise that lakes do not have tides. Had I known this, the lie would have been obvious; but as I didn’t know that, I would never have thought to look it up. Or, had I looked up ‘lakes’ I wouldn’t haev even know what teh salient poits to look out for were. The point is clear – to understand statements, you need to know things; but it’s not obvious which things. The knowledge we need on a problem cannot possibly be specified in advance.

Consider: “I’m not trying out my new barbecue when the boss comes to dinner!” Mark yelled. We can automatically imagine the situation and likely understand the sentence. In doing so, we are drawing on knowledge about employment, status, barbecues, cooking with new equipment, social etiquette, and embarrassment and so perhaps can empathise with Mark. And again, we have to have all this in our heads so we can piece it all together – if we didn’t, we wouldn’t even know what we were missing, and what to look up.

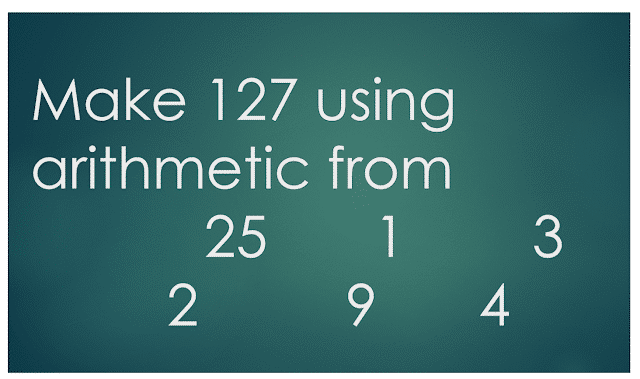

The issue goes further than just understanding; it also affects problem-solving capacity. Consider the countdown-type problem shown in the diagram.

Now, most people quickly see that (25 x 4) + (9 x 3) = 127 but only because most adults know automatically, without needing to calculate it, that 25 x 4 = 100, and 9 x 3 = 27, without any conscious effort or need for a calculator. If you didn’t just know these facts, at some deep level, then you wouldn’t know to work them out. You’d have to resort to the absurd mention of trying out various combinations (eg (9 + 4) x 25/(2 + 3) – of which there are many, many millions. Interestingly, the more facts you know, the more different and creative solutions you might find. Someone who knew, who just ‘saw’ that 125 = 25 x 5 might come up with 25 x (4 + 1) + 2 = 127; a mathematician who knew that 27 = 128 or 5! = 120 might well get to 2(3+4) – 1 = 127 or (4+1)! + 9 – 2 = 127. These are what we could typically call ‘creative’ but are completely based on firm knowledge that’s deep in memory.

So creative or critical thinking doesn’t somehow happen separately to what we know; facts are the bricks from which we build creative and critical structures. That’s why there is (at the moment, anyway) a fundamental and massive difference between things on machines and things in our brains. If it’s not in long-term memory, it’s useless for critical or creative thinking. Looking it up just doesn’t cut it.

So if knowledge rich people have the capacity to understand more, to exercise greater critical analysis, to solve problems more readily, and even to be more creative, what does this mean as we seek to develop these skills? What does knowledge rich schooling look like? Well, contrary to many stereotypes, we do not need to adopt drill-and-kill and rote learning pedagogies. That won’t work because it’s simply not how people naturally learn. Take the information needed to understand the barbeque example from above – it’s not reducible to a list of facts, but it might be gained through social interaction with others, reading books about everyday life, discussions, dinner-table conversation, experiences of cooking, and so on – in other words, engaging in a rich life of varied experiences. The same transfers to the numbers example; beyond the basic timetables (which should be memorised) fluency and familiarity cannot possibly come by learning randomly 27 = 128 or 19 x 14 = 266 because (i) there are simply too many such facts to learn (ii) the facts would then be unconnected and so useless and (iii) most students would leave class from boredom. So to develop that knowledge we need to expose students to a rich range of situations involving number patterns and number relationships – puzzles, investigations, problems and so on.

All this speaks to varied, open work at school that exposes students to a lot of facts in meaningful contexts. If they collaborate and communicate on the basis of these facts then it will lead to deep knowledge that will support creative and critical thinking. So the knowledge emerges not as the end-product, but as a by-product of engaging in thoughtful, conceptually based tasks. It’s not so different to what we all want in most spheres of life – to retain the best of tradition, and to combine it with the best of new, progressive thinking too.

References

- Mollick, E (2024) Intelligence: Living and Working with AI. W. H. Allen.

- Willingham, D (2021) Why don’t kids like school? Jossey-Bass.

1 Response

Totally agree with you. I love inquiry focused learning, but that cannot be done well without a certain amount of prior knowledge. Learners need a solid framework that they can hang their inquiry on.