I have been thinking about that story from a few weeks ago – about the chaos in the US airports, following Trump’s surprise announcement on flights and screenings from Europe. The BBC reported that ‘Some public health experts have noted that waiting in crowded terminals could potentially lead to more people becoming infected with the virus’. Politics aside (hard as that may be), this is just a micro-example that shows how everything is connected. The basic point about restricting travel was correct; but the lack of thought given to implementation completely undermined the objectives. There are some interesting lessons here.

What would have needed to happen in airports for the volume of screenings to be done without exposing people to additional risk by being in close proximity with each other? Likely airports would have had to have time to order more health equipment, increase staffing rosters, perhaps re-arrange queuing areas, increase airport catering capacity, and so on. Each of these steps also has an onwards ripple effect.

To increase production of health equipment, for example, manufacturers would place more demand on their supply chains; those suppliers producing electronics, for example, may well be drawing on China, much of which was in lockdown. So in this very simple case, the very thing that is causing extra demand in US, might prevent the possibility of meeting that demand in China.

The idea of things being related in complex ways was popularised decades ago in Why Things Bite Back: Technology and the Revenge of Unintended Consequences. The basic point is that we cannot think about anything in isolation. The point still stands – it turns out, for example, that replanting forests can actually cause a net release of carbon, depending on where you plant them (BBC article here)

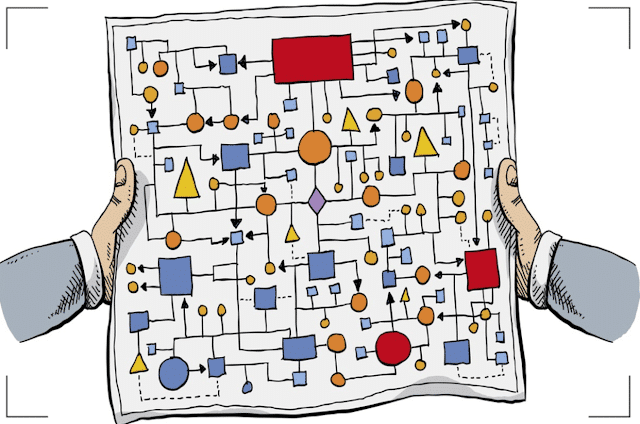

This is not a cause for despair; there are solutions to this type of thing, of course; and effects like this are familiar to anyone who thinks in terms of systems, rather than of individual actors and actions. In recent years, systems-thinking has emerged from many areas – economics, health, biology, education and others – as a discipline in itself. It offers the essential insight that it the configuration of connections between things that is as or more important than the things themselves.

There is a familiar metaphor here – instead of seeing our home as an isolated one, we can see our house as part of a global apartment block. That is, very closely connected. Then if our neighbour’s home is on fire, spending our own resources on putting the fire out is both compassionate and self-interested.

Extending a metaphor to a system can be a bit of a paradigm shift. Donella Meadows, wrote in 2008: The flu virus does not attack us; we have set up conditions in which it will flourish. It took me a while, under the current circumstances, to see what she was getting at: to see coronavirus as an attack implies a mindset of here we are, all established and self-contained; and here’s this virus, getting into places it shouldn’t be, undermining our stability. And that’s one way of looking at it; it rather locates us as the centre of the (ego)system – and it might lead to one set of actions. But Meadows is suggesting that we need to see ourselves and the virus as already part of the same (eco)system. This virus, and others like it, have always been there, as we know from history, constantly evolving in response to a whole range of factors – some of which are human-created (eg the 1918 pandemic has been linked to conditions imposed by WWI). So if we adopt a mindset that says we have set up conditions in which it will flourish we might ask ourselves about our attitudes to global travel, to health issues, to lengthy supply chains and so on.

There are complex issues on which I know little; but I wonder if this pandemic will turn us inwards – towards nationalism – or turn us outwards to recognise, once and for all, that we are all in this together. The latter might mean we recognise the need for some global health standards; but that would require a systemic change with many implications. These may be as trivial as perhaps washing our hands six times daily (like brushing teeth apparently became more common thanks to World War II); or it might mean we wouldn’t disband pandemic units that monitor outbreaks; or very profoundly, we might adopt some sweeping changes to global inequalities such as funding for healthcare.

All this means that as well as addressing the urgent tasks we face, we need to pay attention to how we think. That is, as always, the root of the issue – if we do not change it, we may solve immediate issues, but we won’t solve the underlying problem:

If a factory is torn down but the rationality which produced it is left standing, then that rationality will simply produce another factory. If a revolution destroys a government but the systematic patterns of thought that produce that government are left intact, then those patterns will repeat themselves… There’s so much talk about the system. And so little understanding.

Robert Pirsig

References

- Harrabin, R. (2020) Climate change: UK forests ‘could do more harm than good’ BBC.

- Meadows, D. (2008) Thinking in Systems Chelsea Green Publishing Company

- Pirsig, R. (1974) Zen and Art of Motorcycle Maintenance William Morrow Company

References

1 Response

Great quote!