Last term I was talking with a student, seeking to understand how he felt about a particularly difficult set of circumstances and behaviours. He described how he was thinking and feeling – that he was well and happy – but all his body language, tone of voice, mannerisms and gestures said something completely different. I was left wondering what was really going on for this young man. It was hard to know what to think.

Dealing with things similar to this is familiar territory in teaching (when I tried to submit my assignment the website crashed) and parenting (I was at a friend’s house, but my phone was out of battery), but in this case, despite the mixed messages, there was also sincerity and plausibility, and it did not feel like a matter of simply asking what was true and what was false.

The notion that a set of statements that can be individually plausible, but collectively inconsistent is common enough that it even has a name – an apory. In ethics, for example impartiality seems compelling, but so does putting family first; in metaphysics, free will seems obvious, as does cause and effect. Much of western philosophy is about dealing with apparently contradictions like these, and one way is to decide that one of two opposing ideas must be correct; that is to seek one truth.

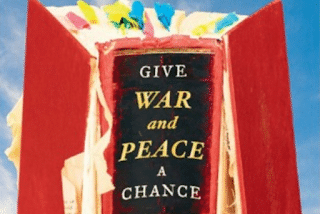

David Hall and Roger Ames make a distinction between truth seekers and way-seekers. The former need to resolve every inconsistency, but the latter are simply not bothered by the contradictions, and suggest that the difference is between describing reality and the art of living. Now my initial reaction as a scientist is that it’s best to decide how to live on the basis of reality – but looking back on events such as the conversation with the student, I have come to realise that in cases like these there may be no single coherent reality, so the scientific approach cannot be the right one. In James Wood’s delicious paraphrase of Thomas Mann: The idea of one overbearing truth is exhausted.

As far as humans (as opposed to chemicals, or numbers) go, this idea is easy to understand – that we are complex, multi-faceted, beings for whom consistency is not a high priority. History (and sadly today’s politics) shows that individuals and societies can take very rapid contradictory directions quite quickly; and an honest appraisal of our own lives would, for most of us, likely say the same at some scale or other. So perhaps consistency would be limiting, even restrictive. The notion of freedom from consistency may even be quite appealing, especially as famously expressed by poet Walt Whitmann in Song of Myself:

Do I contradict myself?

Very well then I contradict myself,

(I am large, I contain multitudes.)

This idea is rather beautiful, but seems to open the door to all sorts of trouble. As parents and as professionals, in difficult situations with individuals we have to fall back to asking what’s really going on? and not just accept contradictions. It cannot be wise to accept without question that people can be one thing one day, and something totally different on another; that none of us have fundamental core tendencies, characteristics or values.

A word often used in these contexts is authentic, and psychologists Sereno and Leary describe authenticity as the degree to which a particular behaviour is congruent with a person’s attitudes, beliefs, values [and] motives. To describe someone as authentic is usually a compliment – a mark of integrity and honour. Can we really jettison it so easily by saying that contradiction is normal, even expected? I don’t think so.

That’s not to say that authenticity is itself unproblematic. Writer Stuart Kaufman asks which form of “being true to yourself” is the real authenticity: was it the time you gave that waiter a piece of your mind, [because you were genuinely cross with the poor service] or that time you didn’t tell the waiter how you really felt about their dismal performance because you value kindness and were true to your higher values?’ So is authenticity about naturally upwelling feelings, or consciously chosen values? Which is ‘more real’?

Looked at this way, the idea of authenticity is no solution, but it simply raises the question of what to be authentic to. Here modern psychology steps in with some troubling empirical observations which suggest that perhaps authenticity is just another story we tell ourselves and others, as a form of status game. We’d love to think our charitable giving reflects our authentic self, and to think that’s more authentic than, as Kaufman says ‘watching Netflix while eating that stack of glazed donuts.’ But which do we spend more time on?

Psychologist Roy Baumeister argues that given our sensitivity to social status, it would not be surprising to find that we choose to label as authentic that which reflects well on us; that desired reputation is a driver. In support he also notes that ‘when people fail to achieve their desired reputation, they will dismiss their actions as inauthentic, as not reflecting their true self (“That’s not who I am”) …As familiar examples, such repudiation seems central to many of the public appeals by celebrities and politicians caught abusing illegal drugs, having illicit sex, embezzling or bribing, and other reputation-damaging actions.”

Interestingly, Baumeister come to the conclusion that there is no authentic, genuine true self that is distinct from actual behaviour and experience. In the end, Bauemister the psychologist and Whitmann the poet come to same conclusion – the self is contradictory. Baumeister goes on to suggest that we replace the notion of self with what is stable – which he claims are our own self-concepts – that is, our individual beliefs about ourselves; or to put it a different way, the stories we tell ourselves, about ourselves.

I guess that would be no surprise for the way–seekers among us, and validation for the novelists. But even for the truth-seekers, it’s not too bleak. If we abandon the idea of a single true self, and accept that we have multiple non-false, partially true selves, then that might that be a way, as psychologist Sean Sayers has said to recognise and allow all parts of the self to be expressed and realised, and thus to maximize the satisfaction of as many aspects of the self as possible to the maximum possible extent.

There may be times when this will not work; but more often, when we are way-seeking rather than truth seeking, it means that in our conversations our students and children, we do not have to be cross-examining to find the truth. We can instead look to tell, with them, the stories of their best future selves. This is an enabling and liberating philosophy.

References

- Hall, D. and Ames R. (1997), Thinking from the Han: Self, Truth, and Transcendence in Chinese and Western Culture SUNY Press

- Kaufmann, S (2019) Authenticity under Fire Scientific American

- Baumeister, R. (2019) Stalking the True Self Through the Jungles of Authenticity: Problems, Contradictions, Inconsistencies, Disturbing Findings—and a Possible Way Forward Review of General Psychology Vol 23, Issue 1.

- Sayers , S (n.d.) The Concept of Authenticity

- Jongman-Sereno K. P. and Leary, M. (2018) The Enigma of Being Yourself: A Critical Examination of the Concept of Authenticity

- Whitman, W. (1892) Song of Myself – Leaves of Grass (1892-92). The Walt Whitman Archive

- Vess, M. (2019) Varieties of Conscious Experience and the Subjective Awareness of One’s “True” Self Review of General Psychology Vol 23, Issue 1

- Wood, J (2010) The Broken Estate. Picador