When we maths teachers confess to our profession with adults, we are usually met with I was never any good at maths when I was at school quickly followed by Excuse me I have to go now.

This always strikes me as such a tragedy, and not (just) because I am once again alone at parties. Imagine an adult saying I was never any good at literature when I was at school. Fortunately, no-one ever says that about literature! But what is it about maths that elicits such a response, and what what can schools do about it?

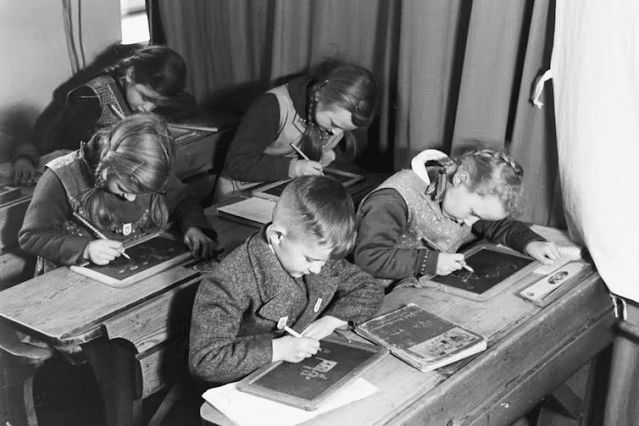

I do not believe it is the content of maths that is the issue here; I believe it is traditional pedagogy. Maths education has traditionally looked like this:

I think this is a big part of the problem, and when adults say they were not good at maths, it’s because maths lessons in the past have tended to focus on:

- working individually rather than collaboratively;

- being static rather than mobile;

- work being private rather than public;

- feedback being delayed rather than immediate;

- students learning only from teachers rather than also with each other.

We know, from our research-backed Learning Principles that the second approaches on each line here are far more likely to lead to engagement, whereas the first are likely to lead to my loneliness at parties (not that I am bitter).

You’ll notice in these videos that the desks are laid out in the same way as ever – because we know that we often need to have individual, solo wrestling with problems to apply the skills and understanding that are best learnt collaboratively. So this is not radically different overall, just radically more engaging. Ken Stirrat, our Head of Maths makes the central point: As soon as you take [Maths] from an individual to a pair or a group, or from the desk to a whiteboard, it opens up a whole new world. And you just need to look at the students – moving between groups, disagreeing, correcting each other, looking for alternative solutions, laughing, checking in with the teachers – to see that these students are getting something substantially better to what was the norm some years ago.

There is a much broader moral point here too, that’s related to our UWC Mission. The goal of peace and a sustainable future is such a lofty one that we have to approach it in many ways. We have found many things that students can learn to that end; but one of the most powerful ways we can do is to teach in ways congruent with this Mission. Susan Neiman notes that “as long ago as 1763 Rousseau observed that schoolchildren who are used to sitting still while a bored teacher’s jabber washes over them are unlikely, as adults, to stand up when a politician lies.” More recently, Paulo Freire said, in a similar vein that “liberating education consists in acts of cognition, not transferals of information”. And this is really where this pedagogy comes from – a whole vision of education as about so much more than just what we learn; it’s also about how we learn, who we learn with (not just from), and most importantly, why we learn.

References

Neiman, S., (2017) Why Grow Up? Penguin Random House

Freire, P. (2000) A Pedaogy of the Oppressed. Bloomsbury Academic 30th Anniversary Edition