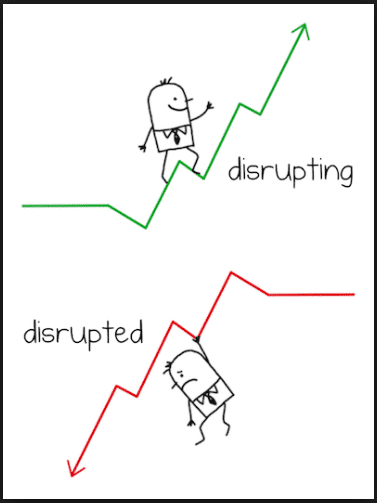

There seems to an idea that has taken root in some parts of popular culture; that schooling – and perhaps more generally education – is somehow broken; that it is the same as it was 100 years ago; that it is some dinosaur that needs fixing, or in modern jargon, disrupting (see here, or here for example). And that technology can provide the promised land. Writer Audrey Watters calls this the ‘Silicon Valley’ narrative, riding on the back of our love (or at least fascination) of Google, Facebook, Apple, Uber and the like. The vision is ever so appealing! The trouble, however, is that it is largely a false, misplaced vision. Like many falsehoods, its appeal lies in the fact that there is just a grain of truth in it.

That grain is profoundly obvious: We can improve schools, and we can use technology to do so. No question there. We’re talking about it all the time in school and though we do not always agree how, we always agree that it’s the right conversation. Furthermore, I imagine we can probably replace ‘schools’ by ‘hospitals’, ‘airlines’, ‘ministries’, ‘churches’ or indeed just about any decent organisation that has ever existed.

automatically bad seems to me to be a problem

It is, however, a big jump from there to the ‘radical disruption’ of, those who predict radical change in education. Clay Christensen, for example, predicted in 2011 that ’50 percent of the 4,000 colleges and universities in the U.S. will be bankrupt in 10 to 15 years’; Arne Duncan predicted in 2012 that ‘over the next few years, textbooks should be obsolete’ (intersting, echoing the great inventor and visionary Thomas Edison a century earlier ‘books will soon be obsolete in schools’). These and other notions get a lot of press, and appeal to many, sometimes because so many of us had bad experiences at school ourselves, and among educators and parents, most often simply because we want to create a better outcome for our own students and children (there is a less charitable reason that some companies support this view).

I want to argue that we need to stick with the slow, step-by-step, incremental improvements that collectively do add up to radical improvement; that there is no silver-bullet solution, and that we need to continue to trial small scale projects. Like compound interest, many small changes add up to massive change – which is why from 1900 to 2015 global literacy increased from 21% to 86%; and why our most current school curricula are so utterly beyond the curricula of a few decades ago in terms of the conceptual understandings that they require.

Do not be mislead by the fact that school classrooms in many cases look very similar to schools of the past. So do toilets, for very good reason :-). But unlike toilets, what’s happening in classrooms is in many cases profoundly different as students engage with information in far more active ways than previously. Technology can play a role here for sure (though not always as tech companies might suggest – one of the most single radical technology for teaching High School maths, for example is the whiteboard properly used). And many (not all) modern curricula would have been largely incomprehensible in structure to teachers of previous generations, in their explicit and coherent attention to knowledge, skills, understanding and affective dispositions as learning outcomes for students.

So deep and profound changes have taken and are taking place. They will continue to do so; and they may involve the obvious online learning opportunities. I was an early adopter here – a decade ago I did my MEd online, and I have recently completed several other online ‘badged’ courses. The irony is that the type of learning that happened in these courses was far more narrow, didactic and information-based than any other face-to-face professional learning I have ever done. That is, these superficially progressive courses actually involved a great deal of individual work watching lectures (via video, even duller than face-to-face), doing ‘interactive’ multiple choice questions (we used to just turn to the back of the book to check answers, now it’s a pop-up) and engaging in sham collaborative work (because the mandated ‘you must make 3 responses to other people’s posts’ yielded inauthentic, forced and shallow conversations). So we need to tread carefully here; and proceed with care knowing that some virtual benefits are indeed unreal.

This does not mean we cannot experiment; on the contrary, it means the need to experiment and be informed by what works is ever more pressing. The Silicon Valley narrative is not going away; we just need to control the innovation. Victor Frankenstein’s creation is instructive – he only became monstrous when he was abandoned by his maker; Frankenstein did not educate or love his creation. So, as Audrey Watters argues, we must care for our ed-tech creations; we are responsible.

References

- Christensen, C. (2008) Disrupting Class

- Lederman, D (2017) Clay Christensen, Doubling Down. Inside Higher Ed. April 28, 2017

- Smith, F. J. (1913) Looking into the Future with Thomas A. Edison. The New York Dramatic Mirror, The Evolution of the Motion Picture: VI Page 24/ New York.

- Watters, A (2016) The Curse of the Monsters of Education Technology. Tech Gypsies