Among the many things that we want for our children from school, two that are often commented upon globally are (a) academic outcomes (b) wellbeing. We can get some (imperfect, rough, limited) measure of the former through standardised testing; this is what the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) study does by measuring 15-year-old school pupils’ scholastic performance on mathematics, science, and reading. First performed in 2000 and then repeated every three years, PISA is as robust a data set as we have and the results, by country, are subject to great scrutiny (ah, the perils of league tables!). The results of the 2018 data collection will be released on Tuesday 3 December 2019.

|

| There are many ways to conceptualise Wellbeing. Here’s how the PISA tests think about it |

The data are fascinating, and I want to explore two findings.

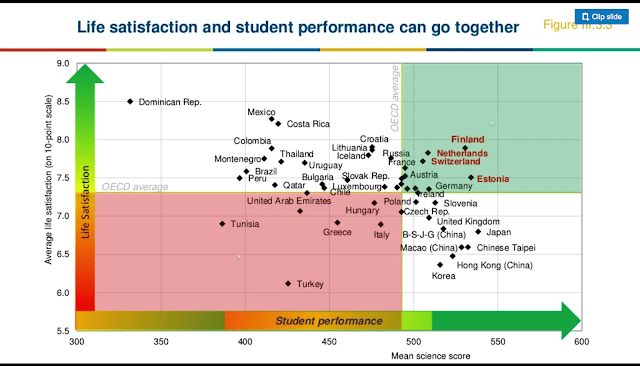

Finding 1: Life Satisfaction (ie wellbeing) and student performance (ie attainment) can go together.

|

| Life Satisfaction and student performance can go together. source |

The vertical axis is self-reported wellbeing; the horizontal axis is attainment. Look carefully at the top right quadrant, and contrast it with the bottom right quadrant. It would seem that high attainment can co-exist with high wellbeing. My tentative conclusion here is that competition and testing (the traditional markers of academic rigour seen in the bottom-right quadrant) do support high academic attainment – but they are not necessary and it is perfectly possible to get just as good results without the concomitant stress and damage to wellbeing. Schools and parents, note! This point was also demonstrated by the Economist who produced a especially compelling graphic:

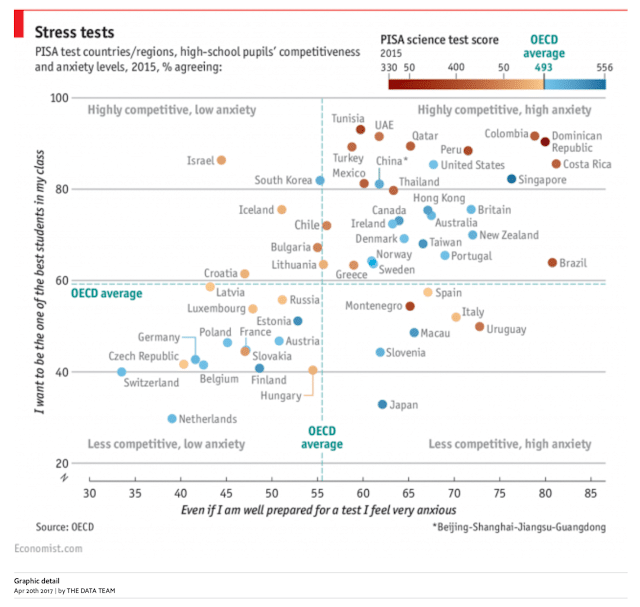

Finding 2 High Competition and Anxiety are often associated with lower Performance.

|

| Anxiety and Competitiveness are associated with low performance source |

This graph needs a bit of interpretation. The horizontal axis is a measure of anxiety; the vertical axis is a measure of competitiveness. So bottom left quadrant is the ‘less competitive, low anxiety’ region; upper right quadrant is the ‘highly competitive, high anxiety’ region. Now you might look at the highly competitive, high anxiety quadrant and think that this is a price worth paying for high attainment. There’s a value judgement there that schools and parents can make – and that are implicit in policies and practices.

But before you think about that, now consider the colour of the dots – the blue dots are high attainment and the red dots are low attainment. Note that the lowest attainment (red dots) occur where there is high competition and high anxiety; and that the highest attainment (blue dots) is spread entirely over the spectrum of anxiety and competition. So, it seems that there is no need for high competition and high anxiety to reach high attainment. This is critical; highly attaining systems can get their results without the stress and competition; and when we know that schools seem to be facing increasing levels of self-harm and even suicide, it’s hard to see why anyone would not try to run schools where reducing anxiety and competition is not an explicit strategic aim.

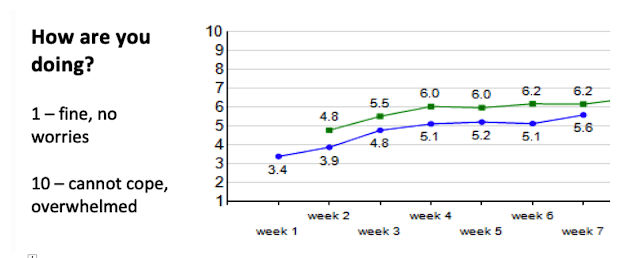

These and other similar ideas have very much informed our thinking as have looked, over the years, at the data from our own students. For over a year we have been asking our students, each week, to answer a one-question ‘how are you doing?’ survey, from 1 (fine no worries at all) to 10 (really struggling and cannot cope).

We know that a score of 1 or 2 may mean students are totally relaxed – not being stretched or challenged much, but also that a score of 9 or 10 is not likely to be healthy. Somewhere in the middle would be ideal. For our HS students, the average for most groups came in around 4 – 5, which seems about right, but we were concerned about one group, Grade 12, the intense pre-university year.

Last year we put in place a short PSE intervention for grade 11 to prepare and support before they got to grade 12. At the same time we logged how Grade 12 were feeling; so that we had some baseline data; and we have this year been tracking the post-intervention data. It’s early days, but the signs are encouraging:

|

|

UWCSEA East: Data from Grade 12

Green line – 2018-19 data.

Blue line 2019-20 data so far this year

|

The fall is consistent and noticeable, and brings Grade 12 – until now the most difficult year – more closely in line with other years. Of course this is averages – but there is also a significant drop in the absolute numbers reporting 8, 9 or 10; furthermore, those that are reporting at these levels are seeking help more frequently than last year, when few people sought support.

None of this seems to be coming at the cost of attainment, and taken overall, the PISA data is consistent with what we are seeing; that we don’t need pressure, anxiety and competition to get where we want to go; and that student wellbeing is not at odds with attainment.

References

- Economist (2017) Competitiveness at school may not yield the best exam results

- OECD (2015)PISA 2015 Results (Volume III) Students’ Well-Being

- Schleicher, A. (2017) The Wellbeing of Students: New Insights from PISA

6 Responses

I see the concept of virtue Ethics (Eudaimonia) and Dan Pink's (Mastery) to promote engagement.

Thanks. Can I ask, did you have any concerns about self-reporting leading to inaccurate results? I was wondering if you felt this issue was overcome by looking at trends over time rather than the single average number? Every school has what I term an emotional calendar and that to me is an interesting aspect to this.

Hi Thom – yes, PISA address this in a report somewhere and I imagine that self-reporting is open to question; there may be cultural influences on what people report feeling, for example. But that for PSIA they consistently see a gender gap would, to me, suggest that perhaps this not enough to completely discount things.

In terms of our own data – yes, absolutely, the time series makes it far more compelling than any single point. And as you say, there is an emotional calendar at play. That the calendar is followed with a constant-ish gap suggest that data is valid to me.

Yes, I wanted to ask about whether you felt is worthwhile looking at data by gender too 🙂 Sometimes we look for tools that have a sort of perfect validity/reliability which seems to me to be a mistake – no model is 100% accurate.

I am suggesting to our team that we implement something like this in our school, as I believe it would be valuable. From your experience, is there anything to consider at implementation to give it the best chance of success?

Easier to talk than write? Drop me a line nal@gapps.uwcsea.edu.sg

Hi Nick!

Great data analysis and does look promising. Have you written elsewhere / already about the intervention in Grade 11 that looks as if it might have contributed to this improved wellbeing? And was there other feedback from students about the intervention that helped reinforce your hypothesis that it was this that made a difference? I think there's plenty of people reading your blog who'd love to implement. Thanks. Nathan