Much educational practice is built on the very reasonable-sounding belief that students are motivated to improve by feedback on how they are doing, whether it is reassurance for those who are doing well, or incentive for those who are not.

Alas, the data shows that this is often not true.

It should not be such a surprise; we can all recognise many complex and contradictory motivations in ourselves; all parents know that students, our children, are the same. They are, in particular, motivated as much by the desire to fit in, or avoid being ostracized, as anything else. One ingenious US study, involving English and Maths courses in over 100 US High Schools, showed this very clearly. Students had been used to answering multiple-choice questions online and receiving private feedback on whether their answers were correct. The experiment involved an unannounced change to the system; students were suddenly graded on performance for correct answers, and home screens made public the names of the top three scorers in the specific classroom, the school, and also state-wide; for the last week, month, and for all-time. Finally, all students were given their own individual ranking – again, in the classroom, school, and among all users, for the past week, month, and all time.

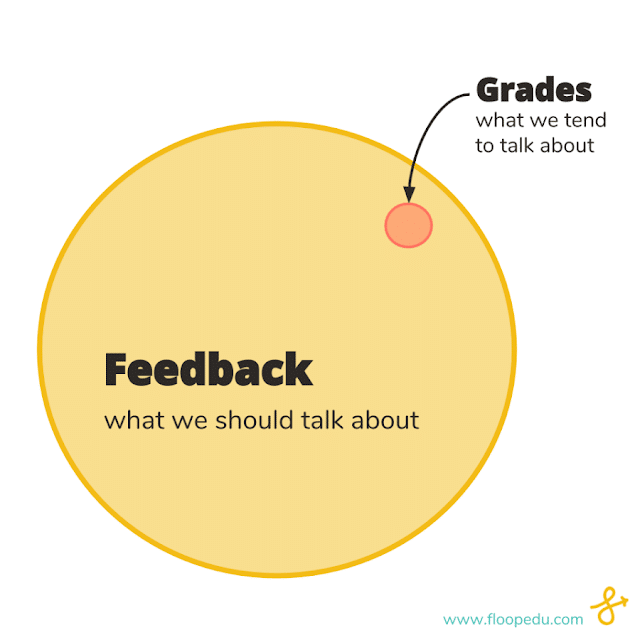

So let’s be more precise about what mean by feedback. In fact, I’ve been a bit disingenuous until now – because actually I don’t regard the case mentioned as feedback at all, but simply as grading, which is different. We can see why if we consider Hattie and Timperley’s 2007 characterisation of feedback as information provided by an agent (e.g., teacher, peer, book, parent, experience) regarding aspects of one’s performance or understanding. The point is that feedback should provide information with which a learner can confirm, add to, overwrite, tune, or restructure information in memory, whether that information is domain knowledge, meta-cognitive knowledge, beliefs about self and tasks, or cognitive tactics and strategies (Winne and Butler, 1994). That is, feedback needs to cause some level of cognitive action in the recipient to improve to deserve the name. Grading, therefore, does not automatically qualify as feedback.

This move might be welcomed by many, who might ask how can giving students their grade and class ranking be a bad thing? The data, however, from 5,000 students across more than 100 schools, is startling. This one simple change resulted in an overall 24% performance decline in achievement! It’s hard to know what other simple measure would have such a big impact. Strikingly, the decline was not evenly distributed across students – those students performing best just prior to the change had a 40% percent performance decline, while poor performing students improved slightly. The drop in scores came mainly from students attempting fewer questions, not from getting fewer questions correct, and from cutting back in effort outside school. These declines were evident on the very first day of the change, and there was, furthermore, a strong correlation between performance level before the public rankings were started and the size of the decline in scores. It is hard to escape the conclusion that students were utterly de-motivated by the feedback. We can speculate that this might have been because they were afraid to be seen as failures publically, or perhaps because they feared ostracism if they excelled. Either way, the feedback was disastrous, and the point is that we need to think not just about the amount of feedback, but about the types and effects of feedback; the two are very different things.

Deci, Koestner, and Ryan (1999) contrast feedback as understood this way, with rewards such as stickers, awards and as some would say, grades. They describe these as contingencies to activities rather than feedback because they contain such little actual information on how to improve; and they note that these contingencies decrease subsequent performance. Schinske and Tanner summarise many papers on this topic with: So rather than motivating students to learn, grading appears to, in many ways, have quite the opposite effect. [At its worst] grading lowers interest in learning and enhances anxiety and extrinsic motivation, especially among those students who are struggling.

In schools therefore, we need to ask what effect will this feedback have on students? Will it motivate them to pay more deep, thoughtful attention, or to pay less attention, or to go through the motions of apparently paying attention? And to answer this, we are into the realm of teacher-student relationship, rather than the nature of the feedback itself, because the same feedback can have an utterly different effect depending on who it is delivered by. Kluger and DeNisi’s famous 1996 meta-review of research found that in almost 40% of well-designed studies, feedback actually lowered performance; confirming the anecdotal data from the US study I described earlier.

None of this means that feedback is not important – on the contrary, it is far too important to just blunder around with. It is therefore, like the proverbial double-edged sword – needing a lot of care if not to be damaging.

References

- Bursztyn, L. and Jensen., R (2015) How does Peer Pressure affect educational investments? The Quarterly Journal of Economics (2015), 1329–1367

- Deci, E. L., Koestuer, R., & Ryan, M. R. (1999). A meta-analytic review of experiments examining the effects of extrinsic rewards on intrinsic motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 627-668.

- Hattie, J. and Timerley, H. (2007) The Power of Feedback

- Kluger, A., DeNisi, A., (1996)The Effects of Feedback Interventions on Performance: A Historical Review, a Meta-Analysis, and a Preliminary Feedback Intervention Theory

- Kulhavy, R. W. (1977). Feedback in written instruction. Review of Educational Research, 47(1), 211-232.

- Schinske, J. and Tanner, K (2017) Teaching More by Grading Less (or Differently) Life Science Education

- Winne, P. H., & Butler, D. L. (1994). Student cognition in learning from teaching. In T. Husen & T. Postlewaite (Eds.), International encyclopaedia of education (2nd ed.) Pergamon Press, Oxford, UK.