Back in the days of the British Empire, Delhi faced a problem with deadly cobras in the city (too many, that is, not too few, in case you were wondering). In what seems to be a rather prescient approach – that is, a narrow economic one – the Governor decided to offer a bounty on cobra skins. The programme started very well; huge numbers of cobra skins were handed in. But strangely, the number of cobras in the city did not seem to fall.

It turned out that the entrepreneurs of Delhi, of which there were many, figured out that it was too hard and too dangerous to hunt cobras; better to stay at home and set up cobra farms; thus efficiently and more safely producing far more cobras to slaughter and sell to the government for profit. When the Governor realized what was happening, he called the bounty off. That would be the end of the matter, except of course that our enterprising snake farmers now had thousands of deadly and worthless snakes. And so they took the cheapest way of disposing of them – that is, to release them into the city, resulting in a much worse infestation. It turned out that simple measures of snake reduction was not such a smart idea.

The specifics of this case are not so important (even though the French did largely the same thing with rats in Hanoi); the message is really about targets, how to achieve them, and what to measure to know that you are on track. I’ve written about this before, and further examples are not hard to find. For example, Spotify measures demand for music by the song, and pays artists accordingly. So two three minute songs are twice as profitable as one six minute song; it’s thought that this is why songs are getting shorter. In education, the OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) measures and ranks countries by scores 15-year-olds’ abilities in reading, mathematics and science. The intended consequences are laudable and likely valuable – a solid bank of data to analyse to improve education. But there are some baleful unintended effects of the measure.

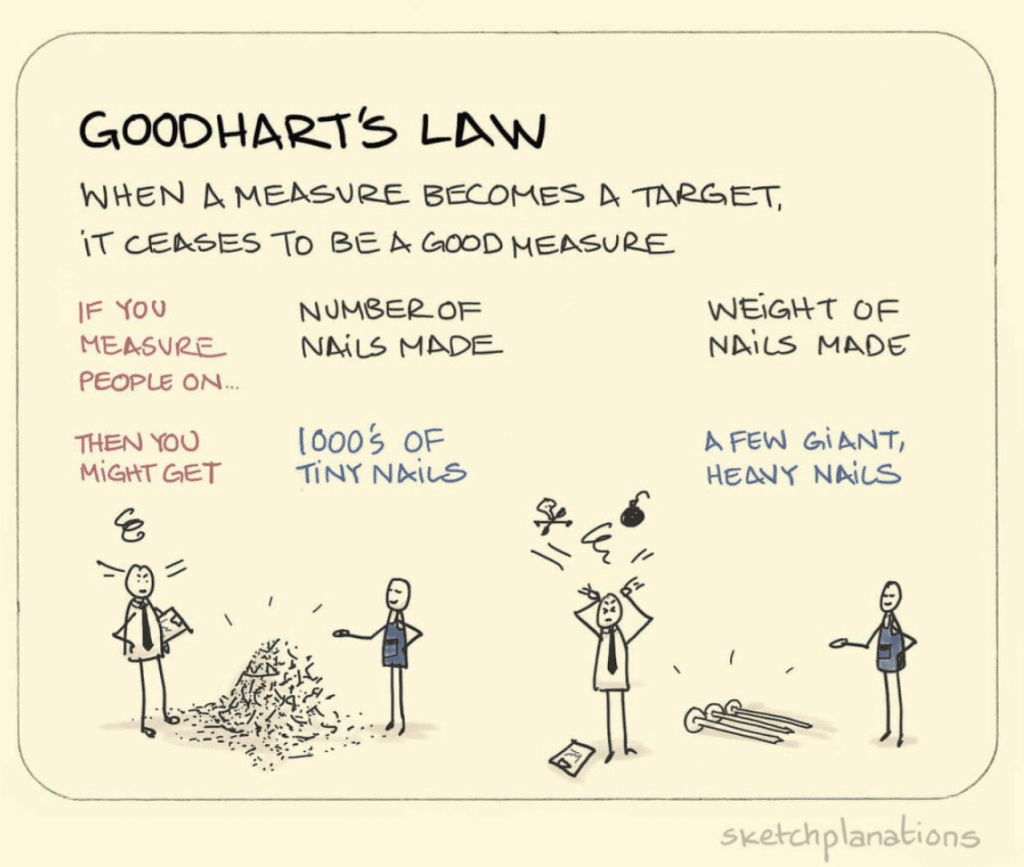

These problems fall into the same category, often summarised in Goodhart’s Law: When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure. The aim of education is not to nail the PISA tests; it’s to educate kids; and the PISA measures one narrow aspect of that. But such is the seductive power of league tables (here are the 2018 results), that the PISA Director, Andreas Schleicher is now seen as one of the most influential figures in global education. To his credit, he does often take an expansive view of how to improve education (Quotes: ‘Parents should see actually their own attitude to learning makes a huge difference on outcomes’, ‘Overall rais[ing] the status of the teaching profession… it’s an important first step’); and PISA itself is clearly not responsible for individual national, regional or school policies. Bt PISA nevertheless remains highly contested (not that you would know this from the mainstream media reporting).

As detailed in a recent summary (Has PISA helped or hindered?) education professors Harris and Zhao have suggested that PISA has effectively narrowed the curriculum to measurable outcomes and taken away autonomy from teachers and joy from student learning in participating countries. It’s certainly true that PISA results shift the conversation towards how good we are at Maths, Science and Reading – all important things, but it leaves out the arts, humanities, languages, design, physical education. And that’s just as far as traditional academic subjects go! What about skills and qualities like creativity, critical thinking, self-regulation, communication, and collaboration? Or character dispositions like kindness, compassion, friendliness, honesty, and authenticity? Or the crises of our time like political engagement, technological competence, environmental awareness and activism? These are the attributes that we hear are so desperately needed in the modern world, but we are less likely to attend to them then we are drowning in a sea of PISA data. If you measure and reward snake skins, people attend to snakes. If you measure and reward narrow tests….

The idea that we can rank education systems by missing out all of of these other factors is not far short of absurd. If we take PISA too seriously, we find we will be ignoring these critical areas in favour of maths, reasoning and science. That is, if we take it out of its very narrow and limited context, there is a danger that we will be using PISA precisely against what it set out to do – help policy makers improve education (there’s a striking parallel with the narrow use of the GDP per capita which is meant to indicate population wellbeing, or development, but which is increasingly seen as inadequate or corrupting).

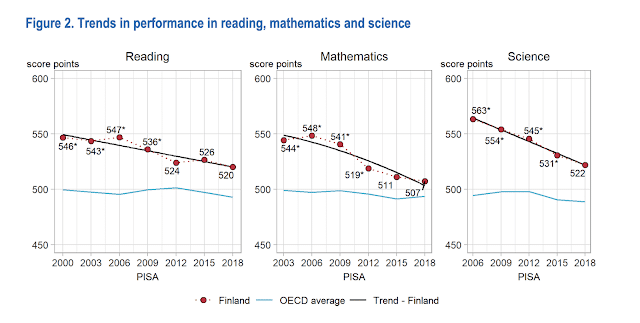

Goodhart’s law is perhaps more precisely expressed in Campbell’s law: The more any quantitative social indicator is used for social decision-making, the more subject it will be to corruption pressures and the more apt it will be to distort and corrupt the social processes it is intended to monitor and to end what might otherwise be a rather negative post, let’s look at how intelligently Finland is treating PISA results, and how they are actively aware of the danger of of ‘corruption pressures’. First, let’s look at the PISA results since 2000, when Finland shot to international attention by topping the tables.

In many countries these results might be the source of much hand-wringing, with some political heads rolling, and the rushed introduction of a new policy to ‘fix things’. So it’s instructive to hear from Pasi Sahlberg, former director general of the Finnish education system, which doesn’t introduce its children to formal schooling until the age of seven, requires its highly autonomous teachers to have master’s degrees and almost entirely rejects standardised testing. In a recent interview, when asked why Finland is falling in the tables he commented:

Most OECD countries have shaped their national education policies… to be aligned with PISA… [but] education policies in Finland are not targeted to do well in PISA at all…. PISA is not seen in Finland as a trigger for education reforms. There will be no new policy changes that would be inspired by PISA in Finland. What we need to underline here is that PISA tells us only a small part of what happens in education in any country. Most of what Finland does, for example, is not shown in PISA at all. It would be shortsighted to conclude by only looking at PISA scores where good educational ideas and inspiration might be found.

I would argue that it is now very interesting for others to take a closer look at how Finland will deal with this new situation of slipping international results. The first lesson certainly is that the best way to react is not to adjust schooling to aim at higher PISA scores.

Sometimes, saying what you will not do is as important as saying what you will do. Sahlberg is thinking with Finnish students, families and educators, not league tables, in mind. He is not placing value on measures like PISA scores (snake skins) simply because they are easy to measure. There is wisdom here.

References

- Carr, T (2017) A Critique of GDP Per Capita as a Measure of Wellbeing ECONPress.

- Harris, A., and Zhao, Y. (2015). Should the PISA be saved? The Washington

Post. - Heim, K (2016) What’s behind Finland’s PISA slide? Straits Times

- Kopf, D. (2019 The economics of streaming is making songs shorter. Quartz

- Lewis, B. (2019) Pisa tests boss: Wales education system ‘lost its soul’. BBC.

- Sahlberg, P (2014) The brainy questions on Finland’s only high-stakes standardized test

- Takayama K. (2015) Has PISA helped or hindered? University of New England

- Vann, M (n.d.) On Rats, Rice and Race Project Muse

- Walker, P (2013) Self Defeating Regulation

- Zhao, Y (2018) What Works May Hurt. Teachers College Press