It’s hiring season for teachers (job adverts here), so we are thinking very hard about who to bring into our College. At one level the goal is easy to define – hire the best person for the role – but when a particular focus for us is to appoint diverse and excellent candidates, the term ‘best’ becomes somewhat slippery. This is hardly a new issue and there are many perspectives. US Supreme Court Justice Anton Scalia famously argued that if you are recruiting for ‘performance’, then recruiting people because they are different, in one way or another, is to jeopardise that performance. He made the analogy with a relay team; you choose the fastest runners because speed is pretty much the only thing that matters; you don’t go for a diverse team, you go for a high performance team.

I don’t know enough about athletics to know if that’s true about a relay team (I wouldn’t want Usain Bolt on the team if he kept dropping the baton) but it seems a pretty shaky metaphor from which to generalise because a relay team has a very narrow task, with an extremely limited objective. This is about as far as you can get from the type of work teachers do in schools or indeed that most professionals do in any organisation. For example, author Matthew Syed notes in his wonderful Rebel Ideas that the number of papers written by any individual has declined year on year in almost all areas of academic study; in science/engineering and medicine 90% and 75% of papers, respectively, are the result of collaboration and are written in teams. Syed notes research led by psychologist Brian Uzzi, which examined more than 2 million US patents since 1975 and found teams are dominant in every single one of 36 categories. He writes ‘the most significant trend in human creativity is the shift from individuals to teams, and the gap between individuals and teams is growing all the time. We might say that we are moving from a focus on individual to collective intelligence’. This absolutely echoes our experience of working together – we intentionally design collaborative processes, because we know that is how we will do powerful, high quality and long-lasting work.

So what does this mean for hiring in schools?

Syed offers the interesting observation that over the last couple of decades, there has been a steady trickle-down from psychology about the ways we think. Issues in decision-making, motivation, reasoning… all these have widely popularized in best-sellers such as Mindset, Thinking Fast and Slow, Predictably Irrational, Drive and so on – so much so that many ideas like confirmation bias have become part of our vocabulary. To focus on how we think, as individuals, has to be a positive step. But there has to be more work to do, because a focus on individuals is at best limited, and at worst, deeply disabling for any organisation. As noted, most problems are too complex to be undertaken by any individual; and certainly raising and educating children is the work of the whole school ‘village’.

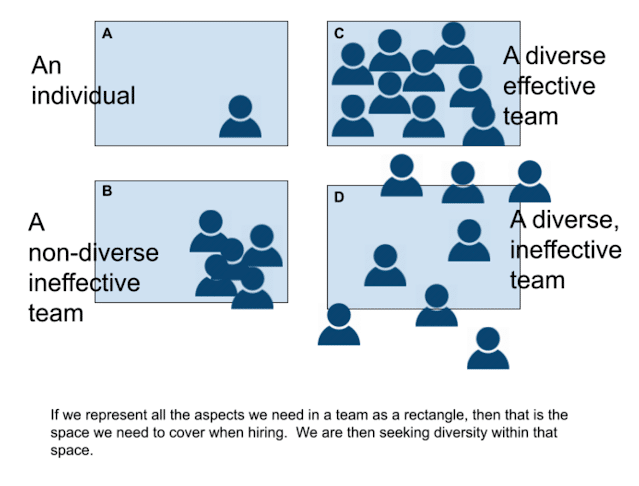

So we need to move from hiring individuals to hiring for teams. Syed suggests that we think of all the skills and capabilities that we are looking for in our organisation, and then imagine these as a physical space – a rectangle in the diagram below. The diagram shows four different cases. So you can see in diagram A, one individual who fits well in the space might still well be a good hire. Syed’s point is that diagram A doesn’t tell the full story; we have to look at the team because one individual, however capable, cannot meet all our needs. He argues that if all the individuals overlap very closely, even if they are all great individual hires, they still don’t collectively cover much of the space. That’s what we see in diagram B – the lack of diversity means there are big areas left uncovered.

It’s an obvious metaphor – that what we are looking for is a team that best covers the entire space we need, as shown in C. The metaphor also shows the constraints we have; situation D also shows an ineffective team despite the diversity.

This way of thinking fits with most organisations who aspire to recruit on the basis of skill and potential. It might seem to be a morally commendable, self-interested and fair way to conduct recruitment – that’s part of the thinking behind blind recruitment practices for example. But we should not accept it blindly, because it appears to discount aspects like race or gender. A story illustrates the reason why this can be so problematic; a few years ago a high school teacher of Thai ethnicity recounted to me a striking conversation she had had with her primary school daughter:

Daughter: Mummy, are you a real teacher?

Mother: Yes I am, what a funny question! Why do you ask that?

Daughter: Because all the real teachers are white, and all the brown adults are assistants.

It’s hard not to wince reading that, even after a few years, and many retellings. We have to applaud the daughter for her conscious awareness, because – and this is the most troubling thing – most children will just absorb what they see without even noticing it. That’s a disturbing truth and the story illustrates the point that when we look at the space we want to cover – the rectangle in the diagrams – it doesn’t contain just curriculum knowledge, assessment skills, pastoral understanding – what we might call the technical nuts-and-bolts side of teaching. It also contains the identity pieces, the adaptive ones that can best be met by a diverse teaching population. This story shows very clearly that students need to be able to see themselves represented by their teachers. We would not be happy if some areas of the school had 100% men or 100% women; by the same token we need to look for different types of diversity in our teams (of which there are plenty, as you can see in the diagram below). What this means is hiring decisions need to be made in a context of teams, not just on the basis of individuals. So it’s not as simple as meritocracy, narrowly (which is really to say naively) understood .

This is not an argument to say that the nuts-and-bolts don’t matter. They do and we will not compromise on the excellence we need there. But we know that teachers don’t just teach what they know, they also teach by virtue of who they are. I wrote about this before, but in that piece I missed this diversity angle. It’s a critical addition, because the generalised significance of diversity is that it’s not icing on the cake; it’s a basic ingredient of collectively becoming the team we need to be to reach, connect with and support our students.

References

- Syed, M (2020) Rebel Ideas.

2 Responses

Really interesting read. Diverse teachers absolutely impact students' identities and self concepts, even if students don't fully realise the impact at the time. A diverse team also impacts curriculum choices and pastoral care in very important ways. An English teacher's choice of texts, for example, may be very influenced by his or her background. More faculty diversity will inevitably lead to a more diverse curriculum. Similarly, when it comes to pastoral care, a student may find it easier to talk to a teacher with a similar linguistic or cultural background. In so many ways, a diverse team can cover more ground than a non-diverse team.

Thanks for sharing; I enjoyed the post.

Really very interesting view and the best way to prepare students to face the global challenges getting trained in a multicultural environment