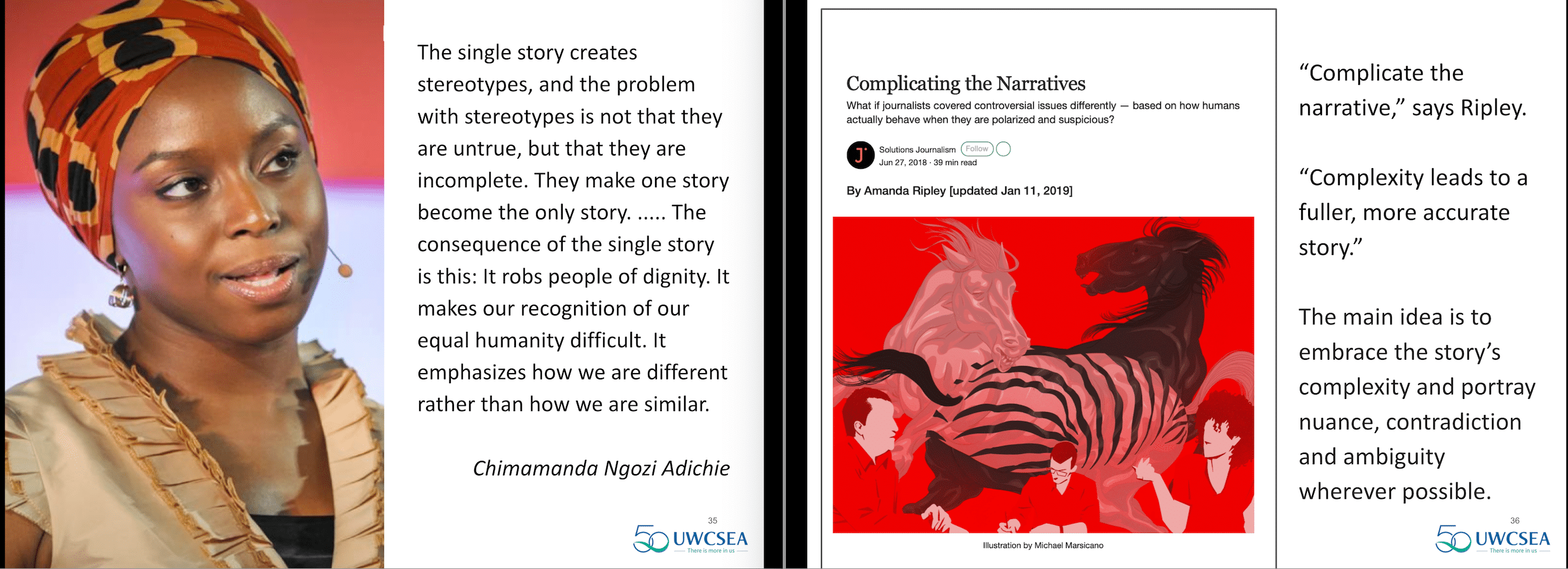

And the reason this topic can be difficult is not because we have different opinions; we have different opinions about many many things. But if elsewhere, two people disagree on, say, the teaching sequence in a unit that disagreement is likely to be boundaried; the disagreement is likely to stay above the waterline of the iceberg. But as we know, for these topics, people’s life experiences, values and identities can come into play. Thus, this is higher stakes, and genuine conflict may be possible. Now this may be no bad thing – many good things can emerge from a conflict; and in any case the absence of conflict is not always harmony; it can sometimes be apathy. But it is also possible that conflict can damage us, and set back the very things we believe in.So I want to say a little about good conflict, and place it in a broader context.Let me start with Nigerian novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s classic, 27 million times watched, 2019 TED talk – the Danger of a Single Story (if you have not seen it, then please do watch it – it’s moving and powerful and funny).

What Adichie talks about is the way that her own thinking was straightjacketed by one way of thinking;

- how as a child she thought books were not about Africans because the books she saw had no Africans in them;

- how because she saw her helper labelled as ‘poor’, and indeed, labelled him that way herself, she was astonished his family had some beautiful objects in their home;

- how because of her ethnicity, some people expected her to listen to tribal music and could not believe she loved contemporary pop.

She also speaks how despite this, despite her being a subject or victim of stereotypes, she has herself also stereotyped Mexicans. So she’s really talking about the way all of us, regardless of our own identities, oversimplify and rob each other of some dignity. How any of us, whatever our identities, will have blind spots in different areas. How we are all prone to reduce things to good or bad, black or white, or in my view most poisonously, for or against an issue. She’s arguing that this is just naive.

The second thing I want to draw on is from recent US election. With the polarized and fractured conversations that were splitting communities, families and even relationships across the US, journalist Amanda Ripley wrote a very influential piece which is a lovely follow up from Adichie’s Danger of a Single Story. She spoke to people with experience navigating conflict — lawyers, conflict mediators, psychologists and religious leaders — and her piece Complicating the Narratives points to ways that have been shown to allow for progress in difficult areas.

A simple example here. Example: There was a concern raised from some students that some staff members were referring to them as boy or girl as in ‘thank you girl‘ or ‘please do this boy’ and that they were not comfortable as it didn’t feel respectful or right.

Now, many of you will know that some support staff use the terms boy or girl in the same way as many of us use the terms auntie or uncle. They are gendered; they are age-specific – but in our local Singaporean context they are also affectionate and respectful. Now it would be easy to tell them to stop – which would be in line with our general approach not to foreground gender. Or we could tell the students that we would not address it – which would be in line with our approach to respecting local traditions and culture. But actually, both of these foreground a single story and avoid the complexity. Either approach would be easy to take, in the sense that it could be made to fit a narrative. Easy, but mistaken and ultimately, to reduce this to one side against another, does not help but actually undermines the search for progress.

It’s an everyday example; I am sure you can think of others. For me the key thing here is to avoid simplification; to recognise the dangers of single story and to avoid seeing polar opposites in what is, in truth, an issue with shades of grey (the solution here may be an easy one – an open, sensitive, vulnerable conversation between good people trying to do the right thing. In fact, it usually is).

In all these issues, the aim of our discussions should not be victory but better understanding of other views. That’s the long-term work, the hard work. None of us have a monopoly on truth, no matter how fervently we hold our beliefs. So we can learn from each other if we can find the right way to do so.

I read recently “be an explorer, not a preacher, nor a prosecutor”. That’s how we do this work and use it to strengthen our community….

This is a challenge for us all. We want to liberate our students, ourselves, anyone… from the bonds of any prejudicial thinking; I feel more strongly about that than I can easily say. We want to liberate our children’s future from the things that have blighted our past. We will not do this without moving as a community. So in all our interactions, we all need to ask how might we use this interaction to build a stronger community here?

You will know the proverb if you want to go fast, go alone. If you want to go far, go together. Well, we want to go far, so we will not rush this work. It cannot be done by a few. We will do it together or we will not do it at all. We have many here who are perhaps at the forefront of social justice advocacy; we have many for whom this is newer. Most of us are somewhere in between – but wherever we share common purpose – to unite peoples, national and cultures for peace and a sustainable future. Doing so is no easy talk, and we need to be ready to talk openly, make mistakes openly, and listen openly.

8 Responses

Thanks for sharing. Very timely, was having this exactly conversation and expressing same sentiment with head of secondary today. V real danger of divisions among groups being exacerbated rather than closed if the work is not done properly.] This speaks back to your earlier point about 'calling in' rather than 'calling out'. I also think we need a clearer view of the destination of this work. What exactly will success look like? If we are not agreed then will be very difficult to get people to work together. If you feel able to share the rest of the speech by email, would love to hear more about success/ failures you mentioned. Best wishes, Nathan

[I found the Heterodox academy site (Haidt, Rausch and others) full of useful blogs/podcasts too.

Thanks Nathan – happy to share; what's your email?

Hi Nick, If the aim is to move everyone towards social justice advocacy, and the concern is about getting everyone moving together on this direction, how about splitting the two UWCSEA campuses as a trial. Have one campus for the sort of traditional education that UWCSEA has done in the past and the other for all your projects on DEI and social justice advocacy – and let parents decide which one they want to put their kids in. UWCSEA has the good fortune to have two campuses and hence can run this as a social experiment with a fall back if required. Thanks for your preferred reading list. I recommend Douglas Murray's The Madness of Crowds which I see is also in the library recommended books for DEI. Have a good weekend – Tim

Hi Nick, thanks for your thoughtful post, and best of luck moving your school forward. There will always be a percentage of people who aren't ready to move forward, so you have to remember that you can't please everyone, and you need to push forward anyway. So many schools are all talk with no real action, or decisions made without the people most affected by the lack of inclusion.

Just reading the comments, I hope you don't split the campuses to "experiment". That sounds like asking parents to decide if they want to deal with the discomfort of making the world better, or if they'd prefer to stay comfortable and keep the status quo. If the school really cares about DEI work, why would there be a choice?

Thanks v much n.hunt@uwcmaastricht.nl

Hi Nick – Fully agree with your point on avoiding 'simplification'. But this is so deep-rooted in our approach towards complexity in general – by breaking down, classifying and categorizing things, so that we can 'understand' them. Are the tenets of our pedagogy and education in general setting us up for this tendency to simplify? Is there an underlying contradiction in what we are asking our children to do..?

– Sankar M.

Hi Sankar – you are right, that complexity resists being categorised. But we have to start with simplifications. Just as we start teaching about whole numbers before fractions, or irrational or complex numbers, so too we need to start with categories before we point out their limitations. That's an explicit part of the IB TOK course, and indeed should be part of any critical education.

The debate, I think, is about when/where/how to introduce complexity. My own view is that you need the categories to point out how limited they are; if you don't have the categories then that doesn't actually help much. But I know there are other views there, and perhaps it varies by individual preference and even by area of thinking (Pascale: 'Reason's last step is the recognition that there are an infinite number of things which are beyond it.' I wonder what the equivalent for emotion is).

Sure. I agree the issue is not about starting with simplification, but stopping with (and not going beyond) it. Partly it could also be due to an intellectual complacency that sets in once we think we 'understand' something.