In this week of return to school after a week’s home-based learning, (HBL) we’ve had some really thoughtful and well-argued correspondence with families who hold diametrically opposed views to each other. Some have felt that a second week was needed to further mitigate against potential asymptomatic folk returning from time abroad; others that even the one week already imposed unnecessary disruption and was already over-cautious. Both sides quoted scientific studies, and it seems to me that both opposing views are entirely reasonable.

These differences are reflected in broader inconsistent social attitudes to risk. Baruch Fischhoff, Professor of Politics, Strategy and Public Policy at Carnegie Mellon University, has noted that US society spends some 35 time more to prevent death from radiation exposure than to save a life on our highways, and in the UK 2,500 times more money per life saved is spent on safety measures in the pharmaceutical industry than in agriculture. So agreement and consistency, even in ‘normal’ matters of risk are hardly universal, even pre-covid.

More relevantly, I suspect for most readers, Dr. Jürgen Rehm, Senior Scientist at the Toronto Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, notes that we tend to accept much higher risks for voluntary behaviours based on individual decisions (for example, to consume alcohol, or to ski), than for involuntary exposure (covid-19, other pathogens). Our social attitudes to alcohol, for example, show a risk tolerance that greatly exceeds the risks we are generally willing to accept for other risky behaviours and factors.

The existence of multiple valid perspectives is clear when we’re dealing with art or philosophy, but seems harder to accept when dealing with mathematical function of risk, and the science of disease, where one might think that there is an absolute answer. And many conversations seem to head toward one particular, apparently obvious answer (with opposite answers being equally obvious to different people). So here I want to explore a few ways of thinking about risk to show that there are, in fact, no universally acceptable risks, options, costs or benefits, and that all decisions in this field are, therefore, ultimately political ones.

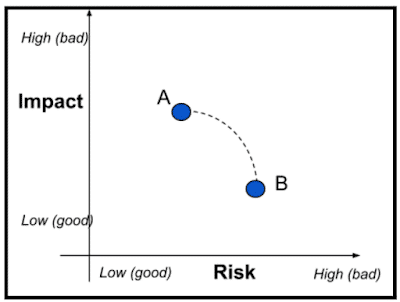

One standard way to think about this is to assess any bad event according to its impact (low impact better, high impact worse) and the probability, or risk of it happening (low risk better, high risk worse). So here in figure 1 you can see option A is less likely to happen than option B, but if it did happen, it’s impact would be worse.

If the undesirable event is, say, a covid cluster, then you might say that HBL is option A – it lowers risk of covid spread, but there is some impact on students and families who want to be in in school; option B might be school as usual; it’s less disruptive, but carries increased risk.

So how might choose between these options? Well clearly, if your aim is to minimise probability of the event (ie the risk) then A is the better option; but if you are seeking to minimise the impact of your actions, then B looks more appealing. Now, we all make trade-offs all the time – we decide to fly (low risk of accident, but high impact (no pun intended) if it does) or maybe have a drink too many (high risk of hangover, but it doesn’t last) and in this instance of a week’s HBL, most people, I think, could accept that A and B were both reasonable – and the dotted line in figure 1 shows that we can move from A to B and back; that is, that we are indifferent to these options and can happily go with either.. But some people really are not indifferent; some may strongly prefer A and B, some the other way around. The indifference curves show why – because these come down to personal preference and how risk averse we are.

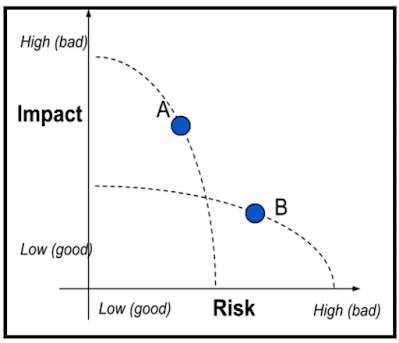

Figure 2 shows two individual’s indifference curves. If you follow the dotted indifference curve through A towards the vertical axis, it shows someone who would be prepared to accept a high impact if the risk could be reduced; if you follow the curve down toward the horizontal axis it shows that they are not prepared to tolerate much increase in high risk even for a substantial reduction in impact. This is a consistently conservative approach to risk.

The curve through B tells another story. Tracing the curve left shows someone unwilling to accept a high impact no matter what the reduction in risk, and tracing right shows a willingness to accept a substantial increase in risk even though the improvement on impact is relatively small. Again, this is a consistent approach – though far less risk averse than the previous case.

So both approaches are reasonable,valid, consistent. And utterly different. Small wonder we have strong differences strongly held.

We all employ this way of thinking outside the risk sphere when we consider any choice in two dimensions – cost and quality in buying a car; job satisfaction and job benefits; hassle in admin and joy of travelling and so on. We trade one dimension off against another, often quite consciously (“I’d love to travel next holiday, but the current visa restrictions are too tiresome – let’s just stay put” – “I could get better pay elsewhere, but I love the work”, “I’d pay a lot more to get a classic MG sportscar”)

The covid case is especially complex, opaque and high-stakes though, for several reasons. Most obviously, because it’s about two of the most precious things to us – the health and the education of our families – and so further elements of psychology come into play. Norwich Medical School School of Epidemiology and Public Health researchers Hunter and Fewtrell note several ‘fright factors’, arguing that risks are deemed to be less acceptable if perceived to be:

- involuntary

- inequitably distributed in society

- inescapable, even if taking personal precautions

- unfamiliar or novel

- man-made rather than natural …

- affecting small children or pregnant women

- the cause of a particularly dreadful illness or death

- poorly understood by science

- the cause of damage to identifiable, rather than anonymous, individuals

- subject to contradictory statements from responsible sources.

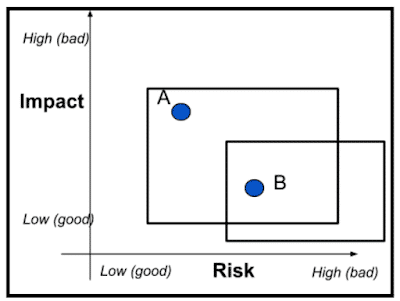

These fright factors all apply to covid-19, and show that any assessment of risk is highly uncertain and variable. And the newness of covid means we have additional questions around impact: Do we really know the hazard? Do we know short-term and long-term consequences? How does home-based learning compared to regular schooling?

All this amounts to the need to relax the assumption of perfect information, as shown in figure 3. The uncertainties around options A and B (e.g. HBL vs regular school) mean that these options cannot be accurately located at a point, but likely lie somewhere in the two boxes. This means that it’s perfectly possible that if A was actually at the bottom left of it’s box, then everyone would prefer A to B. Alternatively, if A were at top right of it’s box, everyone would prefer B to A. It’s even possible (I leave you to work it out) that the true positions of A and B, if known, would be such that everyone who now thinks they prefer A would actually switch to B, and everyone who now thinks they B to A would actually switch to A. Good grief!

My aim here is not to get us all to throw our hands in the air and say ‘Too hard – I give up’ (though it has felt that way at times!). It is to document the sort of thinking that underpins decisions, and I hope show that no simple criterion or approach can determine a decision. We might think that an option becomes clear when the likelihood of the event falls below some arbitrary defined probability; or falls below some level that is already tolerated; or when the cost of reducing the risk would exceed the costs saved; or when public health professionals say it is acceptable; or when the general public say it is unacceptable. In reality, the only time that choices become crystal clear is when they they are legally mandated by the authorities. At all other times, there is the fine element of informed, considered and balanced professional judgement – not hastily taken, but also not hostage to specific loud voices or pressure groups. And that’s our approach to risk here.

TLDR: What looks insane from one stance can look very different from another. Or as author John Scalzi says I am not insane sir. I have a highly calibrated sense of acceptable risk.

References

- Fischoff, B. (1981) Acceptable Risk. Cambridge University Press

- Hunter, P.R. and Fewtrell, L., (2020) Acceptable risk

- Rehm, J., Lachenmeier, D.W. & Room, R (2014). Why does society accept a higher risk for alcohol than for other voluntary or involuntary risks?. BMC Med 12, 189